Why Repair Matters: The Genocidal Legacy Of Chattel Slavery

October 11, 2024

Why do we need an apology today for the genocidal treatment of our enslaved African ancestors, who died before they had a chance to live?

The historical injustices of transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans have left ongoing wounds across the Caribbean region, affecting the economic, social, health, and ecological landscape. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Database estimates that from 1519 to 1867, every three or four days, there was at least one ship departing from the West African coast with enslaved Africans destined for the Caribbean.1 In total, there were an estimated 5,128,495 enslaved Africans who embarked from West Africa to the Caribbean and of this total, approximately 4,416,533 survived the voyage during the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans; a mortality rate of 14%.2 Once the enslaved Africans arrived in the Caribbean, they underwent a ruthless period of ‘seasoning’ where they were forced to adapt to new brutal working and living conditions, to learn new languages, and adopt new customs. This process was so horrendous that several enslaved Africans died within 3 years of their arrival on plantations across the region.3

Planters made minimal provisions for enslaved Africans, as they were considered property, and not people. The enslaved people suffered from malnutrition and starvation among other horrors. The former colonisers instilled fear, using the most brutal forms of extreme physical abuse, including rape and torture, to ensure their ‘property’ worked hard to suppress the urge to escape. The horrific treatment of the enslaved people in Caribbean chattel enslavement became legitimate templates of control by law via The Slave Codes, which introduced legal justification to mistreat and murder without recourse throughout the region.4

Today, the legacies of enslavement continue to impact the lives of Caribbean youth in several ways including: high homicide, mortality, and suicide rates; youth unemployment; high debt to GDP ratios; monocrop economic structures; abject poverty; and normalised culture of child abuse and domestic violence. The brutality of chattel slavery and other forms of colonial violence deliberately manufactured the underdevelopment of the Caribbean region for European profit, crippling self-development in the archipelago.5

Chattel slavery was genocidal. Understanding the impact of this history is crucial for building a just and equitable future for all. Reparation for these historic crimes and their ongoing legacies is critical for the advancement of each country. Add your voice to the calls for repair by signing the petition for Caribbean reparations, informed by CARICOM’s Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice, and following The Repair Campaign on Social Media (Instagram, Facebook, X, LinkedIn, and TikTok).

Antigua and Barbuda was first colonised by the British in 1632. Between 1632 and 1834, 164,868 enslaved people were forcibly trafficked from Africa to Antigua and Barbuda, where only 138,038 disembarked. This represents a mortality rate of 16% during the Middle Passage, with even more enslaved Africans dying due to continued trafficking within the Americas. Enslaved Africans endured unimaginable cruelty on plantations working to produce sugar for British export. They not only faced unsafe working environments while operating boilers and processing sugar, but also experienced severe punishments for the slightest acts of perceived disobedience, including mutilation, being “broken on the wheel”, and even being burned alive.6

Antigua and Barbuda was first colonised by the British in 1632. Between 1632 and 1834, 164,868 enslaved people were forcibly trafficked from Africa to Antigua and Barbuda, where only 138,038 disembarked. This represents a mortality rate of 16% during the Middle Passage, with even more enslaved Africans dying due to continued trafficking within the Americas. Enslaved Africans endured unimaginable cruelty on plantations working to produce sugar for British export. They not only faced unsafe working environments while operating boilers and processing sugar, but also experienced severe punishments for the slightest acts of perceived disobedience, including mutilation, being “broken on the wheel”, and even being burned alive.6

In the years following emancipation, the institutions which replaced the plantation economy have undergone very little development, particularly as it relates to sectors affecting youth. For example, Antigua and Barbuda’s financial commitments to Health, Education, and Social Infrastructure, are all below the average of the smaller Caribbean OECS member states.7 This lack of diversification in economic sectors has led to reduced job opportunities for young people today. This can be seen in an unemployment rate of 33.9% for young people aged 15-24 in 2015,8 with other sources citing 25.7% of 15-24-year-olds not in employment or education in 2018.9

Footnotes:

6 Gaspar, D. B. (1985). Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua. Duke University Press.

7 UNICEF. (2021). Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Antigua and Barbuda FACT SHEET. https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2956/file/Genu%20Antigua%20fact%20sheet.pdf

8 Antigua and Barbuda Statistics Division, Ministry of Finance and Corporate Governance. (n.d.). Unemployment and unemployment rate by sex and age group, 2015– Antigua and Barbuda. Gov.Ag. https://statistics.gov.ag/subjects/labour/unemployment-and-unemployment-rate-by-sex-and-age-group-2015/

9 Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2020. Antigua and Barbuda 2018 Labour Force Survey. Statistics Division: Ministry of Finance and Corporate Governance, 21. Available at: https://statistics.gov.ag/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2018-Antigua-and-Barbuda-LFS-Report.pdf

The Bahamas was colonised by the British from 1649-1973.10 During the period of chattel enslavement from 1730 to 1860, 15,793 enslaved Africans were trafficked on boats intended for The Bahamas, with 13,904 surviving to disembark—a mortality rate of 11.96%.11 Because The Bahamas was not well suited for plantation agriculture due to its thin and rocky soils, it maintained a smaller population of enslaved Africans.

The Bahamas was colonised by the British from 1649-1973.10 During the period of chattel enslavement from 1730 to 1860, 15,793 enslaved Africans were trafficked on boats intended for The Bahamas, with 13,904 surviving to disembark—a mortality rate of 11.96%.11 Because The Bahamas was not well suited for plantation agriculture due to its thin and rocky soils, it maintained a smaller population of enslaved Africans.

Given that The Bahamas did not yield success in agriculture relative to other Caribbean colonies, emphasis was placed in the early 1950s on promoting the tourism industry, which prioritised imperial enrichment over local development. This economic model reflects colonialism’s harmful legacy of extraction, whereby resources from The Bahamas were extracted and supplied to the British Empire.

Liam Miller, Bahamian Development Economist and youth leader, comments that “tourism, a service-based industry, also perpetuates neocolonialism because Bahamians are discouraged from developing their self-identities post-independence and still embody largely Eurocentric values and foreign consumer patterns. Since gaining independence in 1973, The Bahamas has faced obstacles diversifying the economy and equipping Bahamians with skills in more sustainable industries and has had to resort to retaining this extractive economic model for its survival. Yet these problems largely stemmed from the colonial structure of the economy.”

The vulnerability caused by The Bahamas’ over-reliance on tourism can be seen during the COVID-19 pandemic as monetary losses amounting to an estimated $9.5 billion were incurred.12 As a result, economic growth deteriorated, and debt and unemployment sharply rose. This is evident as Bahamians aged 15-24 experienced unemployment rates of 19.2% for young men and 18.2% for young women in 2023.13

Liam Miller concludes, “hence the trauma of chattel slavery and colonialism continues to impede The Bahamas’ development as an independent country.”

Footnotes:

10 Bounds, J. H. (1977). The Bahamian Tourism Situation. Publication Series (Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers), 6, 97–104.

11 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

12 IDB, 2022. “COVID-19 Effects and Impacts on The Bahamas Estimated at $9.5 Billion”. Available at: IDB

13 Bahamas National Statistical Institute Press Release, Preliminary Results Labour Force Survey. (2023, May). Gov.Bs. https://www.bahamas.gov.bs/wps/wcm/connect/17dc1ce3-305c-4e26-ac0a-9194114b8fc7/PRESS+RELEASE+-+Labour+Force+Survey+MAY+2023.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

Between 1626 and 1837, approximately 608,959 people were transported from West Africa to Barbados. However, only 493,163 survived these treacherous journeys.14 Based on these records, approximately 20% of enslaved Africans died during the voyage to Barbados.15 Moreover, the life expectancy of an enslaved person from birth was between 20 to 29 years on average, whereas white persons in Barbados had a life expectancy of about 35 years on average, similar to that in England.16 Despite a steady influx of about 4,000 annually, the number of enslaved Africans in Barbados diminished from 46,602 in 1683 to 46,462 in 1685.17 The decline highlights the result of the inhumane conditions endured by young people, who were literally worked to death, only to be replaced in by newly enslaved and trafficked Africans in an ongoing genocidal cycle.

Between 1626 and 1837, approximately 608,959 people were transported from West Africa to Barbados. However, only 493,163 survived these treacherous journeys.14 Based on these records, approximately 20% of enslaved Africans died during the voyage to Barbados.15 Moreover, the life expectancy of an enslaved person from birth was between 20 to 29 years on average, whereas white persons in Barbados had a life expectancy of about 35 years on average, similar to that in England.16 Despite a steady influx of about 4,000 annually, the number of enslaved Africans in Barbados diminished from 46,602 in 1683 to 46,462 in 1685.17 The decline highlights the result of the inhumane conditions endured by young people, who were literally worked to death, only to be replaced in by newly enslaved and trafficked Africans in an ongoing genocidal cycle.

Barbados became independent in 1966 and since then has made considerable efforts to establish itself as a progressive nation making intentional strides to repair the significant damage inflicted by colonialism. Yet, there are still several issues facing Barbadian youth. In 2016, 32% of young people in Barbados were living in poverty, which is higher than the poverty rate for adults aged 25+ years (21%).18 Adolescence and young adulthood are times when growing up in poverty can hamper educational performance, increase the risk of unemployment, and lead to risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, involvement in gangs, and other criminal activities. In Barbados, there are 55,000 youth (10-24 years old). Despite youth comprising 19% of the population, 34% are unemployed, with male youth being more likely to be unemployed than female youth.19 Barbados also inherited a legacy of ill health due to diets high in sugar and salt that enslaved people were made to eat. As such, 65 per cent of adult Barbadians were obese, while 40 per cent were living with hypertension and 20 per cent with diabetes, as of a 2015 health survey.20 These issues are primarily due to persistent poverty and an inability of those affected to access healthy and nourishing food.

In a conversation with The Repair Campaign, 28 year old Kendra, a young lady from Barbados commented, “Reparations matter to Barbados ‘cuz as a colony we weren’t sufficiently supported enough to handle government expenditure without us having to go into serious debt and as a result all our varying sectors are suffering. For example, our health sector is severely understaffed and overworked, we always got super important equipment breaking down from poor maintenance, and we don’t ever have enough space to house the sick temporarily ‘cuz there’s a lot of elder abandonment, with high costs of living being one of the main reasons.” She continued to explain, “Plus, Bim has a very big NCDs (non-communicable diseases) problem. Who ain’t got diabetes, hypertension or high cholesterol? ‘Cuz the unhealthy food cheaper and requires little to no preparation. Having these reparations would greatly help fix our infrastructure or help reduce our debts so we can improve health care or increase affordability for good food.”

Footnotes:

14 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

15 See previous reference

16 Dunn, R. S., & Nash, G. B. (1972). Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713. University of North Carolina Press.

17 Egerton, H. E., & Pitman, F. W. (1918). The development of the British west indies, 1700-1763. Economic Journal, 28(112), 435. https://doi.org/10.2307/2223336

18 UNICEF Office for the Eastern Caribbean Area. (2021). Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Barbados. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2951/file/genU%20Barbados%20fact%20sheet.pdf

19 See previous reference

20 Barbados Ministry of Health and Wellness. (2024) “NCDs Burden A Public Health Crisis.” Available at: https://www.health.gov.bb/News/Press-Releases/NCDs-Burden-A-Public-Health-Crisis

Belize is a Central American territory which formally became a British colony (under the name British Honduras) in 1862, which was exclusively exploited for timber, mainly mahogany.21 Prior to emancipation in 1838, most persons working in timber camps were not enslaved Africans.22 Despite this unique occurrence, to supplement the mahogany enterprise, 1,023 Africans were trafficked to Belize between 1638 and 1838, with only 899 actually arriving in Belize.23 Higman indicates that, in 1807, there were approximately 3,200 enslaved Africans and this number declined to 2,563 (inclusive of 1,537 males, 600 females, and 426 children under the age of nine) in 1820.24 This combination of transatlantic trafficking and intra-American trafficking was especially evident in Belize, with recorded numbers of 1,513 captives disembarking in Belize across the timeline of chattel slavery in the country.25 Furthermore, Belize was the principal arrival place of the Afro-Indigenous Garifuna population, who were deported from St. Vincent in 179726 and have a unique history of oppression strongly linked to Belize’s history of enslavement and colonisation.27

Belize is a Central American territory which formally became a British colony (under the name British Honduras) in 1862, which was exclusively exploited for timber, mainly mahogany.21 Prior to emancipation in 1838, most persons working in timber camps were not enslaved Africans.22 Despite this unique occurrence, to supplement the mahogany enterprise, 1,023 Africans were trafficked to Belize between 1638 and 1838, with only 899 actually arriving in Belize.23 Higman indicates that, in 1807, there were approximately 3,200 enslaved Africans and this number declined to 2,563 (inclusive of 1,537 males, 600 females, and 426 children under the age of nine) in 1820.24 This combination of transatlantic trafficking and intra-American trafficking was especially evident in Belize, with recorded numbers of 1,513 captives disembarking in Belize across the timeline of chattel slavery in the country.25 Furthermore, Belize was the principal arrival place of the Afro-Indigenous Garifuna population, who were deported from St. Vincent in 179726 and have a unique history of oppression strongly linked to Belize’s history of enslavement and colonisation.27

Within the system of chattel slavery, physical coercion and torture were often used as tools to control enslaved Africans in Belize. This included severe flogging sometimes with a minimum of 500 lashes; being placed in old stores infested with rats, flies, and other harmful rodents; tying enslaved women on their bellies to the ground with their arms and legs being stretched out, and secured to four stakes with sharp cords; among other forms of torture.28 These cycles of violence have been repeated and passed down in the collective trauma and way of function in the Belizean economy and society. Today, 49% of children in Belize live in multidimensional poverty. Due to layered socio-economic stresses, there are high rates of mental health illness, injury, abuse, and casualty among persons aged 15-20 years.29 Similarly, the latest available data indicates that about 46% of persons aged 15 to 25 years are not in classes, training, or jobs.30 The human damage relayed in high rates of interpersonal violence, lack of care-informed approaches to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), among others, is unfortunately balanced with unsustainably high economic damage.31

As a result of colonialism, Belize, like other formerly colonised Caribbean territories, has a long history of mono-crop culture and overreliance on one industry for national income.32 The trend of mass production of one or two goods for export, with a subsequent heavy dependence on importations to sustain islands, is part of the economic structure of plantation societies.33 This trend is still relevant today: Where it was mahogany trading in the 17th and 18th centuries, Belize is heavily reliant on sugarcane and petroleum oil in the 21st century, with sugarcane accounting for 48% of total exports in Belize as of 2019.34 Wholesale and retail trade, as well as agriculture, forestry, and fishery represented the highest portion of Belize’s GDP in 202235 as there has been little opportunity for economic diversification. Once again, the violent instability that Belize’s history of colonial oppression enforced into administration leaves visible, harmful traces in the overall healthcare, welfare, and self-sufficiency of Belizean communities and lands. What lives on as damage from wrongs committed decades and centuries ago must be repaired.

Footnotes:

21 Dutt, R. (2023). “Emancipation and imperialism in a borderland: The challenge to settler sovereignty over slavery in Belize in the 1820s”. Americas (Academy of American Franciscan History), 80(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/tam.2022.8

22 Green, W. A. (1984). “The Perils of Comparative History: Belize and the British Sugar Colonies after Slavery.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 26(1), 112–119.

23 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

24 Higman, B.W. (1995). Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807-1834 : with a new introduction. The Press, University of the West Indies, pp.40-44

25 This combination of transatlantic trafficking and intra-American trafficking is apparent across all colonies, but in the case of Belize it is especially evident, with recorded numbers of 1,513 captives disembarking in Belize across the timeline of chattel slavery in the country. SVD, available at: https://www.slavevoyages.org/american/database#statistics

26 Minority Rights, https://minorityrights.org/communities/garifuna-garinagu/

27 Belize is perhaps one of the most notable sites in the Caribbean where there are substantial records for the migration of indigenous peoples with the violence these peoples suffered alongside the brutality of trafficking tied to chattel slavery- a compounding of colonial oppressions and traumas whose versions can be found across the Caribbean region.

28 Dutt, R. (2023). “Emancipation and Imperialism in a Borderland”

29 UNICEF. (2021). Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Belize, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/belize/media/1521/file/UNICEF%20in%20Belize%20A%20Belize%20fit%20for%20children%20.pdf

30 UN. “Population Data Portal- Belize”. Available at: Population Data Portal

31 UNFPA. (n.d.). Population data portal. Unfpa.org. Population Data Portal

32 Caribbean Development Bank, (2022). “Belize, Gross Domestic Product Indicator”. Available at: Country Data Reports | Caribbean Development Bank

33 Lloyd Best & Kari Levitt, (2008). Essays on the Theory of Plantation Economy, UWI Press

34 Belize Chamber of Commerce & Industry (2024), “Agriculture”. Available at https://www.belize.org/trade-investment-zone/sectors/agriculture/

35 Caribbean Development Bank, (2022). “Belize, Gross Domestic Product Indicator”.

Dominica was colonised first by the French, and finally by the British in 1763.36 Between 1763 and 1838, The Slave Voyages Database reports that approximately 117,417 Africans were forcibly trafficked by the British to Dominica with only 102,469 surviving the Middle Passage (12.7% died on board).37 European colonialism also decimated the Indigenous population of Kalinagos, so much so that by 1764 the Indigenous Kalinago territory was reduced to only 232 acres (0.125% of the entire island).38 The brutal conditions of chattel enslavement in Dominica led to high mortality rates as high as 10-20% among the enslaved population,39 with many dying within the first four years of their arrival due to overwork, malnutrition, and diseases.40 Chattel enslavement in Dominica was so gruesome that the enslaved population declined by 22.6% between 1810 (19,000 enslaved) and 1830 (14,700 enslaved people).41

Dominica was colonised first by the French, and finally by the British in 1763.36 Between 1763 and 1838, The Slave Voyages Database reports that approximately 117,417 Africans were forcibly trafficked by the British to Dominica with only 102,469 surviving the Middle Passage (12.7% died on board).37 European colonialism also decimated the Indigenous population of Kalinagos, so much so that by 1764 the Indigenous Kalinago territory was reduced to only 232 acres (0.125% of the entire island).38 The brutal conditions of chattel enslavement in Dominica led to high mortality rates as high as 10-20% among the enslaved population,39 with many dying within the first four years of their arrival due to overwork, malnutrition, and diseases.40 Chattel enslavement in Dominica was so gruesome that the enslaved population declined by 22.6% between 1810 (19,000 enslaved) and 1830 (14,700 enslaved people).41

Colonisation severely depleted the resources and impoverished the communities in Dominica, particularly with regards to underaged and youth (15-24yrs) persons. In 2016, 29% of people in Dominica were living in poverty, which is higher than the average of 23% for the Eastern Caribbean.42 Younger populations are often more affected by these conditions, with 38% of children ages 0-17 and 36% of adolescents ages 10-19 living in poverty in 2021.4344 UNICEF further indicates that 40% of youth aged 15-24 were unemployed, and, with respect to mental health and wellness, 21% of adolescents ages 13-15 seriously considered attempting suicide with 15% having attempted suicide one or more times in the past 12 months—with a disproportionate impact on young girls.45 Furthermore, Dominica has one of the highest rates of infant mortality in the Caribbean at 32 deaths per 1000 live births in 2022.46 These issues are multidimensional, with lack of sufficient care-informed practices and infrastructure, social insecurity, and mass displacement signifying the long shadow of colonial oppression in Dominica.47

Footnotes:

36 Higman, Slave Populations, p.41

37 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

38 Crispin, & Kanem. (n.d.). “The Caribs of Dominica: Land rights and ethnic consciousness”. Available at: Cultural Survival

39 Sowell, D. (2004). The Problem of Slavery Studies Today-” How Many? Where? When? and Why: The Numbers Game”. Juniata Voices, 4, 59.

40 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.606-616

41 See previous reference, pp.69-71

42 UNICEF Office for the Eastern Caribbean Area. (2021). Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Dominica. Available at: Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Dominica

43 See previous reference

44 See previous reference

45 See previous reference

46 UNICEF. (n.d.). Dominica. Unicef.org. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/country/dma/

47 Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Dominica- Available at: Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Dominica

Between 1626 and 1837, approximately 149,478 people were trafficked from West Africa to Grenada. Yet, only 128,687 survived these perilous voyages. Approximately 14% of enslaved Africans died during the voyage to Grenada.48 The enslaved Africans were mercilessly worked and subjected to the penalties of whipping, mutilation, amputation, and death. Enslaved chattel settlements were poorly ventilated and unsanitary, so much so that many developed respiratory issues such as pneumonia.49 By the end of the 18th century, Grenada had become the third largest sugar producer in the British West Indies, due to the uncompensated and forcefully extracted labour of enslaved Africans.50 Despite its wealth, Grenada grappled with a high infant mortality rate for enslaved Africans typically caused by indigence, neglect, and malnutrition. Worm fever, along with smallpox, measles, yaws, dysentery, and whooping cough were the most fatal complaints among children under 10 years old and young adults.51 During chattel enslavement, the crude birth rate per thousand ranged from 16.3 to 30.7, while the crude death rate ranged from 26.6 to 43.2 per thousand.52 Almost 60% of fever deaths of enslaved Africans occurred in those younger than 25 years old.53 This high mortality means that despite the economic success of sugar production on the plantations, barely any of that wealth was used in the care of enslaved Africans.

Between 1626 and 1837, approximately 149,478 people were trafficked from West Africa to Grenada. Yet, only 128,687 survived these perilous voyages. Approximately 14% of enslaved Africans died during the voyage to Grenada.48 The enslaved Africans were mercilessly worked and subjected to the penalties of whipping, mutilation, amputation, and death. Enslaved chattel settlements were poorly ventilated and unsanitary, so much so that many developed respiratory issues such as pneumonia.49 By the end of the 18th century, Grenada had become the third largest sugar producer in the British West Indies, due to the uncompensated and forcefully extracted labour of enslaved Africans.50 Despite its wealth, Grenada grappled with a high infant mortality rate for enslaved Africans typically caused by indigence, neglect, and malnutrition. Worm fever, along with smallpox, measles, yaws, dysentery, and whooping cough were the most fatal complaints among children under 10 years old and young adults.51 During chattel enslavement, the crude birth rate per thousand ranged from 16.3 to 30.7, while the crude death rate ranged from 26.6 to 43.2 per thousand.52 Almost 60% of fever deaths of enslaved Africans occurred in those younger than 25 years old.53 This high mortality means that despite the economic success of sugar production on the plantations, barely any of that wealth was used in the care of enslaved Africans.

Similar issues of high mortality due to desolation, poor nutrition, and negligence in healthcare practices exist in Grenada today. The infant mortality rate for Grenada in 2022 was 14 deaths per 1000 live births,54 whereas it was 4 deaths per 1000 live births in the United Kingdom for the same period.55 Non-communicable diseases (such as rheumatic heart diseases and kidney diseases) account for 33% of deaths among adolescents aged 10-19.56 Grenada’s population is comprised of 24,800 young people aged 10-24 and over 60% of this demographic have been consistently without gainful employment despite seeking jobs for six months on average.57 These realities reflect a country still struggling to empower its youth and provide proper healthcare and steady employment.

Footnotes:

48 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

49 Koplan, J. P. (1983). Slave Mortality in Nineteenth-Century Grenada. Social Science History, 7(3), 311–320.

50 Quintanilla, M. (2003). The World of Alexander Campbell: An Eighteenth-Century Grenadian Planter. Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 35(2), 229–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/4054136

51 Sheridan, R.B. (2009). Doctors and slaves: a medical and demographic history of slavery in the British west indies, 1680-1834. Cambridge University Press.

52 See previous reference

53 Koplan, J. P. (1983). Slave Mortality in Nineteenth-Century Grenada. Social Science History, 7(3), 311–320. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1171190

54 UNICEF, “Grenada (GRD)- Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality”. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/country/grd/

55 Worldbank, “Grenada”. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN?locations=GB

56 UNICEF, (2021). “Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Grenada”. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2961/file/GenU%20Grenada%20fact%20sheet.pdf

57 UNDP, (2021). “Transition from Education to Employment in Grenada.” Available at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/bb/undp-bb-Transition-from-Education-to-Employment-in-Grenada-January-2021.pdf

From 1658 to 1842, what is now Guyana was respectively split into colonies governed by the French, Dutch, and British.58 Today, France still retains a so-called territory in La Guiane. During that time, there were a total of 1,300 voyages across the Middle Passage.59 A recorded number of 406,294 Africans were trafficked, with 355,533 surviving the journey, suggesting an average mortality rate of 12.49% during the Middle Passage.60 The ex-territories of Demerara-Essequibo and Berbice, previously largely colonised by the British, altogether had an enslaved African population of 107,300 in 1810, which declined by 17% to 88,860 in 1830, indicating the genocidal mortality rate caused by colonial violence.61 Following widespread emancipation of enslaved Africans, a system of indentureship was introduced to replace free African labour with huge numbers of indentured labourers from the South-Asian region.62 Over a period of 1838-1917 (with several interruptions in the mid-1800s), 238,979 Indians were transported to Guyana, which, by 1917, comprised 42% of the Guyanese population.63

From 1658 to 1842, what is now Guyana was respectively split into colonies governed by the French, Dutch, and British.58 Today, France still retains a so-called territory in La Guiane. During that time, there were a total of 1,300 voyages across the Middle Passage.59 A recorded number of 406,294 Africans were trafficked, with 355,533 surviving the journey, suggesting an average mortality rate of 12.49% during the Middle Passage.60 The ex-territories of Demerara-Essequibo and Berbice, previously largely colonised by the British, altogether had an enslaved African population of 107,300 in 1810, which declined by 17% to 88,860 in 1830, indicating the genocidal mortality rate caused by colonial violence.61 Following widespread emancipation of enslaved Africans, a system of indentureship was introduced to replace free African labour with huge numbers of indentured labourers from the South-Asian region.62 Over a period of 1838-1917 (with several interruptions in the mid-1800s), 238,979 Indians were transported to Guyana, which, by 1917, comprised 42% of the Guyanese population.63

The split colonisation of what is now a unified country, as well as the brutal conditions of labour that the plantation infrastructure generated in the Guianas, left indelible traces in the economic, social, and lived experiences of Guyanese populations, particularly those aged 15-24 years, today. In the time frame of 2006 to 2023, youth unemployment increased from 21.3% to 25.9%, peaking in 2020 at 31.3%. Moreover, in 2019, 46.4% of persons aged 15-24 years old in Guyana were neither in classes, in jobs, nor in training.64 Likewise, the mortality rate for persons aged 15-24 years was recorded at 16.8 deaths per 1,000 in 2019.65 With respect to mental health indicators, suicide continues to be a major contributor to death rates in Guyana, with 40.9 deaths per 100,000 population as of 2019,66 far exceeding the world average of 9 suicides per 100,000 people.67 As a result, Guyana has the second highest suicide rate in the world. These statistics speak to the inherited trauma and lack of social and economic infrastructure left in the wake of chattel slavery and highlight the urgent need for repair.

Footnotes:

58 Basdeo Mangru, (04/05/2013). “An Overview of Indian Indentureship in Guyana, 1838-1917”, Stabroek News. Available at: https://www.stabroeknews.com/2013/05/04/news/guyana/an-overview-of-indian-indentureship-in-guyana-1838-1917/

59 Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, “Guianas”. Available at: https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database#results

60 See previous reference. Intra-American trafficking of enslaved populations indicate that, from 1717-1808, (with the highest point during) 1797, a total of 6,341 enslaved persons were embarked on intra-regional ships, with 6,095 captives disembarking, and a mortality rate of 3.87% as well as a total of 114 voyages. SVD, “Guianas”. Available at: Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

61 Higman, Slave Populations, pp. 69-72

62 Mangru, ‘An Overview of Indian Indentureship’ Stabroek News. Available at: https://www.stabroeknews.com/2013/05/04/news/guyana/an-overview-of-indian-indentureship-in-guyana-1838-1917/

63 See previous reference

64 UNFPA Population Data Portal.

65 UNICEF Data Warehouse. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=GUY.CME_TMY15T24+CME_MRY5T24..&startPeriod=2009&endPeriod=2023

66 The Lancet Regional Health, (2022). “Suicidal behaviour and ideation in Guyana: A systematic literature review”. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00070-9/fulltext#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20Guyana’s%20age%20standardised,suicide%20rate%20in%20the%20world.

67 World Health Organisation, (2019). “Suicide Worldwide in 2019”. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341728/9789240026643-eng.pdf?sequence=1#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20an%20estimated%20703,100%20000%20(Figure%201).

Haiti (formerly known as Saint-Domingue) is perhaps one of the most glaring examples of the debilitating legacies of colonialism and chattel enslavement in the Caribbean.68 Between 1697 and 1820, 800,176 enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to Haiti, making it one of the largest ports of disembarkation for the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans.69 Of this number of captives, 695,716 disembarked, suggesting a mortality rate of 13% during the middle passage.70 Chattel enslavement in Haiti is notorious for having some of the most wanton, cruel, and sadistic methods of torture of the enslaved Africans, particularly in the 18th century.71 Hot peppers, salt, lemon, or ashes were sometimes rubbed into open wounds of the enslaved Africans, which were burnt with an open flame to increase the pain.72 Other instances of extreme torture include placing gunpowder in the anus of the enslaved and lighting it; public castration of male enslaved; burning the genitals of female enslaved Africans with hot coals; dangling them above open fire; being doused with boiling cane juice; and being buried alive after having been forced to dig their own graves.73

Haiti (formerly known as Saint-Domingue) is perhaps one of the most glaring examples of the debilitating legacies of colonialism and chattel enslavement in the Caribbean.68 Between 1697 and 1820, 800,176 enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to Haiti, making it one of the largest ports of disembarkation for the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans.69 Of this number of captives, 695,716 disembarked, suggesting a mortality rate of 13% during the middle passage.70 Chattel enslavement in Haiti is notorious for having some of the most wanton, cruel, and sadistic methods of torture of the enslaved Africans, particularly in the 18th century.71 Hot peppers, salt, lemon, or ashes were sometimes rubbed into open wounds of the enslaved Africans, which were burnt with an open flame to increase the pain.72 Other instances of extreme torture include placing gunpowder in the anus of the enslaved and lighting it; public castration of male enslaved; burning the genitals of female enslaved Africans with hot coals; dangling them above open fire; being doused with boiling cane juice; and being buried alive after having been forced to dig their own graves.73

The extremely high frequency of ships crossing the Middle Passage with captives intended for Haiti indicates that life expectancy for the overworked enslaved population was extremely low, which increased the demand for a frequent influx of a trafficked labour force.74 In 1825, twenty-one years after the Haitian Revolution, France demanded an indemnity of 150 million francs to be paid by Haiti to compensate for damage to property (including enslaved Africans).75 Today, that debt would amount to $21 billion.76 Through a series of loans, imperial invasion and more, this debt was fully repaid in 1948.77 However, this debt severely crippled Haiti and is one of the major causes of the deliberate and engineered underdevelopment of the first Black Republic.78

Though Haiti was the richest French colony in the late eighteenth century, today it ranks 158th of 193 countries in the UN Human Development Index, which is the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.79 In 2023, Haiti’s GDP was $19,851 million, compared to France’s $3,030,904 million.80 While France’s economy and polity have enjoyed wealth, Haiti’s economy has not recovered from the effects of this exploitative history. The young people of Haiti face several crises including violence, ill health, education disparities, and lack of economic opportunities, among others.81 Violent crime has crippled education systems, with many children being coerced to join armed groups in response to such violence, with an estimated 30-50% of children making up the members of armed groups.82 Moreover, in 2023, at least 167 boys and girls died from bullet wounds, and nearly one-in-four children in Haiti suffer from chronic malnutrition.83 This malnutrition crisis is aggravated by a persisting cholera outbreak.84 Between October 2022 and April 2024, Haiti reported a total of 82,000 suspected cases of cholera.85

This instability is primarily produced, manufactured, engineered by colonial and imperial powers, powers that still profit from their theft and rape of Haiti’s land and peoples. This recent crisis in Haiti is a glaring reminder of the depth to which reparations are necessary in Haiti, and across the Caribbean region.

Footnotes:

68 Haiti (Saint-Domingue) | Slavery and Remembrance

69 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

70 See previous reference

71 James, C. L. R.(1938). The Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution. New York,

72 See previous reference

73 See previous reference

74 See previous reference

75 Comite de l’abolition de dettes illegitimes, (27/08/2021). “Haiti: Il y a 196 ans, la “dette de l’independance””. Available at: Haïti : Il y a 196 ans, la « dette de l’indépendance »

76 BAIIJDH. “Restitution of Haiti’s Independence Debt from France.” Available at: https://www.ijdh.org/our-work/accountability/economic-justice/restitution-of-haitis-independence-debt-from-france/

77 See previous reference

78 Meeks, B. (2023). After the Postcolonial Caribbean: Memory, Hope, Imagining, Pluto Press

79 United Nations Development Programme, “Specific Country Data/Human Development Reports”. Available at: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-country-data#/countries/HTI

80 Country Economy, “Country comparison Haiti vs. France, 2024”. Available at: https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/haiti/france

81 UNICEF, (2024). “I thought it was the end for me”. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/stories/i-thought-it-was-end-me-Haiti

82 UNICEF, (2024). “Violence drives Haiti’s children into armed groups: up to half of all members”. Available at: Violence drives Haiti’s children into armed groups; up to half of all members are now children– UNICEF

83 UNICEF, 2024. “Crisis in Haiti”. Available at: Crisis in Haiti | UNICEF

84 See previous reference

85 UNICEF, (2024). “Violence sending shocks around Haiti’s collapsing health system”. Available at: Violence sending shocks around Haiti’s collapsing health system

Jamaica was colonised by the Spanish from 1494 and subsequently by the British from 1655 to 1962 when the country became independent. Between the 1600s and the 1800s approximately 1,134,689 enslaved Africans were trafficked to Jamaica, with 979,943 surviving the perilous voyage – 13.6% died on the middle passage.86 Chattel slavery in Jamaica was characterised by extreme sadism, violence, and tyranny. The most infamous form of torture meted out to the enslaved Africans in Jamaica was known as “Derby’s Dose” in which a gag would be put in the enslaved person’s mouth and another enslaved African was forced to defecate in the mouth. The victim was forced to keep this gag for 4 or 5 hours. It was also very common for salt pickle, lime juice, and bird pepper to be rubbed into the open wounds from a recent whipping; rubbing molasses on a runaway enslaved African and exposing them to the flies all day and to the mosquitoes all night.87 Between the years 1762 and 1833, on average there were two deaths per every birth of enslaved Africans on sugar plantations in Jamaica.88 Between the decades of 1810 and 1830, the population of enslaved people decreased by 28,000 from 347,000 enslaved persons in 1810 to 319,000 in 1830. These figures illustrate the lethal oppression suffered by the enslaved at the hands of enslavers.89

Jamaica was colonised by the Spanish from 1494 and subsequently by the British from 1655 to 1962 when the country became independent. Between the 1600s and the 1800s approximately 1,134,689 enslaved Africans were trafficked to Jamaica, with 979,943 surviving the perilous voyage – 13.6% died on the middle passage.86 Chattel slavery in Jamaica was characterised by extreme sadism, violence, and tyranny. The most infamous form of torture meted out to the enslaved Africans in Jamaica was known as “Derby’s Dose” in which a gag would be put in the enslaved person’s mouth and another enslaved African was forced to defecate in the mouth. The victim was forced to keep this gag for 4 or 5 hours. It was also very common for salt pickle, lime juice, and bird pepper to be rubbed into the open wounds from a recent whipping; rubbing molasses on a runaway enslaved African and exposing them to the flies all day and to the mosquitoes all night.87 Between the years 1762 and 1833, on average there were two deaths per every birth of enslaved Africans on sugar plantations in Jamaica.88 Between the decades of 1810 and 1830, the population of enslaved people decreased by 28,000 from 347,000 enslaved persons in 1810 to 319,000 in 1830. These figures illustrate the lethal oppression suffered by the enslaved at the hands of enslavers.89

The aggression and brutality of chattel slavery in Jamaica embodied every form of physical and psychological violence available to the colonisers to dehumanise the enslaved Africans. These tendencies to physical and psychological violence are threads which are still woven into Jamaican society. Homicide data from the IDB show that in 51% of homicide victims in 2013 were males aged 35 or younger, and the 15-24 age group, which represented 19.5% of the population, accounted for 20.4% of all homicide victims.90

In 2022 there were 15,068 reports of child abuse (including extreme neglect, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse),91 and the unemployment rate of youth aged 18-24 was 13.8% in 2023.92 Furthermore, annually approximately 70%-80% of deaths are attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs).93 These statistics indicate a nation struggling with an ingrained culture of violence and a poor foundation for youth security. These underlying issues of self-destruction and violence are remnants of chattel enslavement which created a legacy of intergenerational trauma and socioeconomic disenfranchisement and inequality.94

Footnotes:

86 As part of the intra-American slave trade, 5,587 enslaved people recorded to have been trafficked throughout the Caribbean. Of these, 4,950 arrived in Jamaica, with an 11.40% fatality rate throughout the journey. Source: Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

87 Burnard, T. (2004). Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World. University of North Carolina Press.

88 Dunn, R. S. (2007). The Demographic Contrast between Slave Life in Jamaica and Virginia, 1760-1865. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 151(1), 43–60.

89 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.69-71

90 Jamaica Gleaner. “Young males under the gun – IDB study finds males between 18-35 most likely to be victims and perpetrators of homicides.” Available at: https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/lead-stories/20161003/young-males-under-gun-idb-study-finds-males-between-18-35-most-likely

91 Jamaica Observer, (17/05/2023). “Child Abuse Still on the Rise”. Available at: https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/2023/05/17/child-abuse-still-on-the-rise/

92 World Bank, Youth Unemployment Rate for Jamaica [SLUEM1524ZSJAM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SLUEM1524ZSJAM,

93 UNICEF. (2023). Country Office Annual Report 2023. Unicef.org. https://www.unicef.org/media/152421/file/Jamaica-2023-COAR.pdf

94 Matthies B. K., Meeks-Gardner J., Daley A., Crawford-Brown C. (2008). Issues of violence in the Caribbean. In Hickling F. W., Matthies B. K., Morgan K., Gibson R. C. (Eds.), Perspectives on Caribbean Psychology (pp. 393-464). Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies at Mona, CARIMENSA.

Between 1679 and 1795, approximately 16,960 Africans were trafficked to Montserrat, where only 13,638 survived to disembark (19.5% mortality rate). By 1807, the population comprised approximately 6,880 enslaved Africans, however, by emancipation in 1834, the enslaved population had fallen to 6,355, illustrating the high rate at which enslaved Africans were dying under the brutal conditions of enslavement. During the period of 1817-1821, the death rate was estimated to be 28.6 per 1000, exceeding the birth rate of 27.5 per 1,000 for the same period.

Between 1679 and 1795, approximately 16,960 Africans were trafficked to Montserrat, where only 13,638 survived to disembark (19.5% mortality rate). By 1807, the population comprised approximately 6,880 enslaved Africans, however, by emancipation in 1834, the enslaved population had fallen to 6,355, illustrating the high rate at which enslaved Africans were dying under the brutal conditions of enslavement. During the period of 1817-1821, the death rate was estimated to be 28.6 per 1000, exceeding the birth rate of 27.5 per 1,000 for the same period.

As a current UK overseas territory, Montserrat has never gained independence. Due to this status, the island is highly dependent on the UK to provide financial and economic support. In the 2023-24 financial year, the UK agreed to provide £30.3 million in financial aid to Montserrat.95 This dependence on UK aid has increased since the devastating impact of the volcanic eruptions that began in 1995. CEO of Montserrat’s 664Connect Media Vernier Bass, expressed that “Every time we have a problem here, the first response is we should ask the UK. That dependent mindset where we can’t fend for ourselves…has been exacerbated by the fact that we had a volcanic eruption”.

The series of eruptions from 1995 resulted in the evacuation of over three-quarters of the population, shrinking from around 14,000 to just 3,500 at its lowest point.96 The economy has not recovered well from the volcanic disasters, and the lack of opportunities in Montserrat encourages emigration and brain drain, as young people seek better prospects abroad. Bass shared from a firsthand account given her time living in Montserrat, “When you think about the average young person, especially here in Montserrat at the moment that they graduate, they think I want to go to England or I want to go to the USA”.

This situation mirrors the historical impacts of colonisation and enslavement, with technology playing a key role in both past and present challenges faced by the island. As Bass explained, “The reason why the UK and other nations were able to colonise the Caribbean was because they had technology…in the form of cannons and guns… and even now that technology is still being used against us because one of the main reasons for the brain drain and the migration is technology.”

Footnotes:

95 UK Government, “UK increases budget and capital support for Montserrat”. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-government-partnership-with-montserrat-bolstered-by-additional-funding-support

96 UN, “Montserrat”. Available at: https://www.undp.org/barbados/montserrat

British settlers first colonised St. Kitts and Nevis in 1623, followed by French settlers in 1625, although the islands were occupied under British government. Between 1623 and 1834, a total of 175,167 Africans were trafficked to St. Kitts and Nevis, with 144,849 surviving to disembark, suggesting a mortality rate of 17.30%.97 The primary product exported by the islands’ plantation estates was sugar. By 1810, the mass production of this crop demanded an enslaved population of 31,200, which declined by 9% in 20 years to 28,300 persons in 1830.98 Of this population, in 1830, 87% and 90%, respectively for St Kitts and for Nevis, were concentrated on sugar plantation estates.99

British settlers first colonised St. Kitts and Nevis in 1623, followed by French settlers in 1625, although the islands were occupied under British government. Between 1623 and 1834, a total of 175,167 Africans were trafficked to St. Kitts and Nevis, with 144,849 surviving to disembark, suggesting a mortality rate of 17.30%.97 The primary product exported by the islands’ plantation estates was sugar. By 1810, the mass production of this crop demanded an enslaved population of 31,200, which declined by 9% in 20 years to 28,300 persons in 1830.98 Of this population, in 1830, 87% and 90%, respectively for St Kitts and for Nevis, were concentrated on sugar plantation estates.99

During this time frame, 84.3 deaths of enslaved persons were recorded per 100,000, declining to 64.6 recorded deaths per 100,000 in 1834—noting that the enslaved population did not number as high as 100,000 in that timeframe.100 These mortality rates are, according to Higman, primarily attributed to brutal working conditions, inadequate nutrition, and the prevalence of diseases.101 The plantocracy’s deliberate underdevelopment of medical infrastructure for racialised and marginalised populations inscribes such disregard into systemic administration, even through to today.

Between the years 2000 and 2023, the UN recorded a 12.70% increase in mortality rate overall in St. Kitts and Nevis, compared to a 33.6% decrease in birth rates over the same period.102 The imbalance between recorded deaths and births mirrors a similar decline during chattel slavery and indicates an urgent need for repair. In 2017, St. Kitts and Nevis had one of the highest numbers of children charged in the juvenile correction system per capita (270 per 100,000) in the sub-region. There were 127 children charged in 2014, with battery, disorderly manner/fighting, and causing harm as the three top offences.103 According to a 2021 UNICEF report, the probability of mortality is highest among youth ages 20-24 dying (10 per 1,000 youth). It is notable that among Eastern Caribbean countries and territories, Saint Kitts had the highest probability of youth ages 20-24 dying.104 The similarities between the present context and St. Kitts and Nevis’ history of inherited violence are evident and emphasise the need to repair the socioeconomic landscape today’s youth face.

Footnotes:

97 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

98 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.69-71

99 See previous reference

100 See previous reference, pp.307-311

101 See previous reference

102 https://database.earth/population/saint-kitts-and-nevis/deaths

103 UNICEF, (2021). “Situation Analysis of Children in Saint. Kitts and Nevis”. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/916/file/Situation-Analysis-of-Children-in-Saint-Kitts-and-Nevis-2017%20.pdf

104 See previous reference

Colonial control over St Lucia changed hands between the French and the British 14 times throughout the 17th and 18th centuries until Britain eventually gained control in 1814 after the signing of the Treaty of Paris.105 The Slave Voyages database indicates that between 1724 and 1806, 9,122 Africans were trafficked to St. Lucia, with about 8,281 surviving the brutal voyage, reflecting a mortality rate of 9% during the Middle Passage.106

Colonial control over St Lucia changed hands between the French and the British 14 times throughout the 17th and 18th centuries until Britain eventually gained control in 1814 after the signing of the Treaty of Paris.105 The Slave Voyages database indicates that between 1724 and 1806, 9,122 Africans were trafficked to St. Lucia, with about 8,281 surviving the brutal voyage, reflecting a mortality rate of 9% during the Middle Passage.106

The enslaved Africans who survived the journey faced brutal conditions on the island characterised by horrific working and living conditions, dehumanising treatment by enslavers, and barbaric punishments for acts of resistance. For instance, in 1810, there was an enslaved population of 18,500 in St. Lucia, which decreased by 20.27% to 14,750 in 1820, and further decreased by 9.15% to 13,400 in 1830.107 The previous source also notes that, even with the gradual decline of the transatlantic trafficking system in the early 19th century, St. Lucia was one of the islands in the British Caribbean with the highest mortality rate during that period of time.

The legacy of socioeconomic disenfranchisement and history of violence inherited by colonialism can still be felt today in the level of poverty, crime, and violence experienced by St. Lucians. A recent report by St. Lucia’s Deputy Commissioner of Police revealed that an alarming 334 young people below age 35 were lost to violent murder since 2014.108

A 2020 survey indicates that 50.9% of people over the age of 18 are reported to have been victim to at least one crime in 2019.109 The cycle of violence inherited from colonialism extends into the home environment where 63% of adults believe it is acceptable to use corporal punishment to discipline children aged 6-11, as of a 2019 report.110 Young people in St. Lucia continue to be at risk with about 35% of young people not engaged in education, employment, or training as of 2021.111 The United Kingdom has a significantly lower unemployment rate of 3.8% as of 2022, compared to Saint Lucia’s 21.9% unemployment rate in 2021, indicating greater economic challenges and a less favourable job market in St. Lucia that may contribute to the cycle of violence and disadvantage.112 Although the colonial powers have since physically departed, the impacts of St. Lucia’s history of slavery and oppression are still very apparent and in need of repair.

Footnotes:

105 The World Factbook, “St. Lucia”. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-lucia/#:~:text=England%20and%20France%20contested%20Saint,the%20British%20Windward%20Islands%20colony

106 Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database#statistics

107 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.69-71

108 Loop News St. Lucia. (2024) “DCOP Philip unveils startling statistics on youth violence in St Lucia.” Available at: https://stlucia.loopnews.com/content/acp-philip-unveils-startling-statistics-youth-violence-st-lucia

109 The Central Statistical Office, St. Lucia, “Level of Victimization (2019/2020)”. Available at: https://stats.gov.lc/subjects/society/crime/level-of-victimization-2019-2020-index/level-of-victimization-2019-2020-1-6/.

110 UNICEF, (2021). “Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in St. Lucia”. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2931/file/Gen-U%20St.%20Lucia%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf , https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/bb/The-CariSECURE-Quaterly-Newsletter.pdf

111 See previous reference

112 Country Economy, “Country Comparison Satin Lucia vs. United Kingdom 2024”. Available at: https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/saint-lucia/uk

Between 1764 and 1808 approximately 62,176 Africans were trafficked to St. Vincent; however, 55,562 survived to disembark.113 By 1810, there was an enslaved population of 27,400, declining by 9.67% to 24,750 persons in 1820, and decreasing by 6.66% to 23,100 persons in 1830.114 Classified as a new colony by Higman—the status as ‘new’ here refers to the long Vincentian history of indigenous and Garifuna resistance to enslavement until the mass deportation of Garifuna populations by the British—St. Vincent and the Grenadines saw 68.5% of its enslaved population forced into working on sugar plantation estates, as sugar was the primary source of production.115 There was a 15.69% decline in the enslaved populations between 1810 and 1830 highlighting the genocidal treatment experienced by enslaved people.116 This, as well as the difference in population of trafficked captive Africans throughout the entirety of the transatlantic trade to SVG, demonstrates the overexhaustive conditions of enslavement and the lastingly harmful excavation of land and resources.

Between 1764 and 1808 approximately 62,176 Africans were trafficked to St. Vincent; however, 55,562 survived to disembark.113 By 1810, there was an enslaved population of 27,400, declining by 9.67% to 24,750 persons in 1820, and decreasing by 6.66% to 23,100 persons in 1830.114 Classified as a new colony by Higman—the status as ‘new’ here refers to the long Vincentian history of indigenous and Garifuna resistance to enslavement until the mass deportation of Garifuna populations by the British—St. Vincent and the Grenadines saw 68.5% of its enslaved population forced into working on sugar plantation estates, as sugar was the primary source of production.115 There was a 15.69% decline in the enslaved populations between 1810 and 1830 highlighting the genocidal treatment experienced by enslaved people.116 This, as well as the difference in population of trafficked captive Africans throughout the entirety of the transatlantic trade to SVG, demonstrates the overexhaustive conditions of enslavement and the lastingly harmful excavation of land and resources.

The legacies of violence inherited by chattel slavery continue to be seen as St. Vincent and the Grenadines recoded a homicide rate of 40.41 per 100,000 people in 2022 – the second highest in the world.117 Similarly alarming, the probability of mortality for youth aged 20-24 years in SVG, who make up 14.7% of the population, was 8 per 100,000 population in 2021.118

Records further indicate that the rate for child and adolescent poverty in St. Vincent and the Grenadines is higher than the average across other Eastern Caribbean countries.119 A study published in 2021 indicates that 45.1% of youth aged 15-24 years were unemployed.120 There is a direct connection between the massive human and land cost of chattel slavery and the employment and wealth disparities across St Vincent and the Grenadines, further demonstrating the urgent need for repair in the region.

Footnotes:

113 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

114 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.69-71

115 See previous reference

116 Higman, pp.69-71

117 World Population Review. “Murder rate by Country.” Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/murder-rate-by-country

118 UNICEF, “Generation Unlimited” Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2941/file/GenU%20SVG%20Fact%20sheet.pdf

119 UNICEF, 2021. “Generation Unlimited: The Well-being of Young People in St. Vincent and the Grenadines Fact Sheet.” Available at: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/2941/file/GenU%20SVG%20Fact%20sheet.pdf

120 See previous reference, and International Labour Organisation, 2024. ““ILO Modelled Estimates and Projections database ( ILOEST )”. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS?locations=VC

Suriname was first colonised by Britain in 1650, followed by The Netherlands in 1667. During this time, the Indigenous inhabitants had their land stolen, were forcibly enslaved, and driven to the Interior where they were further marginalised. At the same time, between 1651 and 1838 approximately 340,989 Africans were trafficked to Suriname but only 294,653 survived the middle passage (a death rate of 13.5%). By the 18th century, the population of Suriname was about 49,000 people, with 90% of the population being enslaved (both Indigenous peoples and Africans).121 The experience of enslavement was so genocidal that when Suriname finally gained emancipation in 1873, the population of formerly enslaved people had decreased to 24,625.122

Suriname was first colonised by Britain in 1650, followed by The Netherlands in 1667. During this time, the Indigenous inhabitants had their land stolen, were forcibly enslaved, and driven to the Interior where they were further marginalised. At the same time, between 1651 and 1838 approximately 340,989 Africans were trafficked to Suriname but only 294,653 survived the middle passage (a death rate of 13.5%). By the 18th century, the population of Suriname was about 49,000 people, with 90% of the population being enslaved (both Indigenous peoples and Africans).121 The experience of enslavement was so genocidal that when Suriname finally gained emancipation in 1873, the population of formerly enslaved people had decreased to 24,625.122

The emancipation of the enslaved in Suriname significantly hurt the sugar industry, which led to an economic recession in the years following.123 Suriname gradually shifted to other extractive industries as the major source of its GDP, with mining accounting for almost 50% of the country’s public sector revenue, and gold accounting for more than 80% of the country’s total exports.124 Because of this, Suriname’s economy remains vulnerable to exogenous shocks, as seen by the recession of 2016 in which GDP contracted by 9%.125 Although there has since been some economic recovery, the lack of development in other sectors leaves Suriname at risk of other external economic shocks and vulnerable to more human damage. The average mortality rate for persons aged 5-14 years was 3.9 (per 1,000 persons) in 2022 when compared to a rate of 0.76 (per 1,000) in the Netherlands during the same period.126 Suriname’s rate of suicide is also among the highest in the world with a rate of 23.6 suicides per 100,000 people.127 These are a few of the consequences of colonialism, which urgently illustrate the need for repair to invest in sustainable futures for all. Reparations for the historical genocide and post-colonial underdevelopment would significantly benefit Suriname’s social and economic landscape.

Footnotes:

121 Hoefte, Rosemarijn, and Peter Meel, eds. (2022). Twentieth-Century Suriname: Continuities and Discontinuities in a New World Society. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004475342

122 C.W. van Galen, B. Quanjer and M. Paul (2020). Curaçao: slaven- en emancipatieregisters 1839-1863 [Database]. Available at: https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/index/nt00462

123 den van Velzen, H. U. E., and G. Brana-Shute. (1990). “Resistance and Rebellion in Suriname: Old and New.” Williamsburg: College of William and Mary.

124 The World Bank, “The World Bank in Suriname”. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/suriname/overview

125 Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “Suriname’s Economic Crisis”. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/surinames-economic-crisis

126 UNICEF, “Child and youth mortality ages 5-24”. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/dataset/child-adolescent-and-youth-mortality-rates/ ; UNICEF, “Suriname (SUR)- Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality”. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/country/sur/

127 World Population Review. (2024) “Suicide Rates by Country.” Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/suicide-rate-by-country

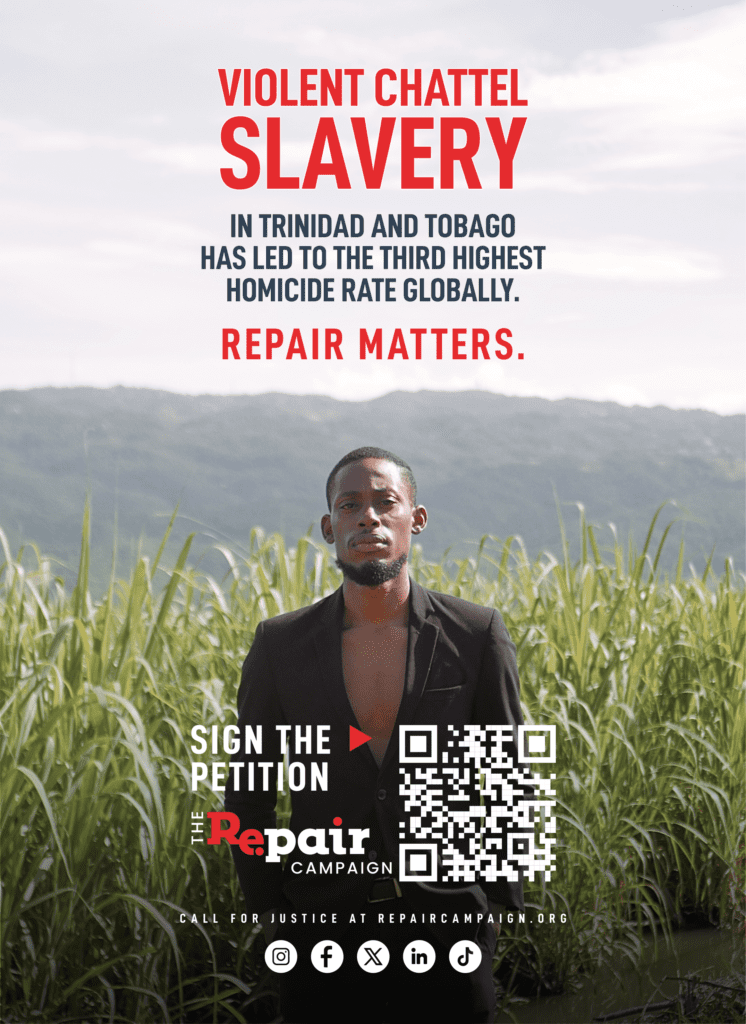

Trinidad and Tobago were respectively under disputed colonial rule during the period of chattel slavery, only unifying under British rule as one colony in 1884.128 Both islands’ period of chattel slavery was marked by brutality and violence, whose trauma lives on today. The crimes committed by the colonial powers that occupied these islands manufactured the conditions for this trauma to be violently reproduced throughout the development of Trinbagonian societies.

Trinidad and Tobago were respectively under disputed colonial rule during the period of chattel slavery, only unifying under British rule as one colony in 1884.128 Both islands’ period of chattel slavery was marked by brutality and violence, whose trauma lives on today. The crimes committed by the colonial powers that occupied these islands manufactured the conditions for this trauma to be violently reproduced throughout the development of Trinbagonian societies.

Between 1656 and 1808, 44,715 Africans were trafficked to Trinidad or Tobago, with 39,966 surviving the journey, leading to a 10.62% mortality rate during crossing.129 By 1810, there was an enslaved population of 44,200 across both islands, sharply declining to 38,450 persons (a decline of 13%) in 1820, and to 35,300 persons (a decline of 8.19%) in 1830. While this data does not tell the full story of regional migration or fugitive resistance that may have contributed to this decline, it is known that, during the period of 1807-1834, Tobago had one of the highest mortality rates for enslaved persons in the Caribbean.130 During the period of chattel slavery, in 1830, 90% of the enslaved population in Tobago and 70% in Trinidad were concentrated on sugar plantation estates.131

The latter part of the 18th century into the early part of the 19th century was characterised by Picton rule—a monstrous member of the British military who was nominated commander-in-chief of Trinidad after the British takeover.132 Picton rule was characterised by the worst forms of torture, rape, assault, and agonising homicide that left a stain in Trinidadian pasts and present.133 After the legal Emancipation in 1838, indentureship was another form of labour introduced to sustain plantation profit, at the expense of African, Indian, Trinbagonian populations. Indentured labour saw 5,392 Indians arriving between 1845 and 1848, with 143,900 Indians transported by 1917 to maintain, in Trinidad, the principal production of sugarcane.134

The reality of the latent effects of colonisation and enslavement-related violence in Trinidad and Tobago reveals that rates of violence and unemployment, particularly in youth (15-24 yrs) populations, remain high. The Central Statistical Office in Trinidad and Tobago recorded a crime rate of 2,243.4 per 100,000 persons in 2022.135

The violence inherited by the history of chattel slavery can still be seen in that the country had the third highest homicide rate in the world, at 39.5 murders (per 100,000) in 2022, compared to 1 per 100,000 in the UK in 2020.136 Trinidad and Tobago’s rates of violence against women (VAW)—not to mention rates of gender-based violence (GBV) overall—are consistently high with a rate of 2.9 females killed by intimate partners or family members (per 100,000 women) in 2020, which is high compared to the equivalent metric in the UK (1 per 100,000 women) in 2021.137

Even within households, it was found that 77% of adolescents ages 10-14 experienced violent discipline, with 44% experiencing physical punishment in 2011.138 According to UNICEF Data Warehouse, 24.8% of women (aged 18-29 years) experienced sexual violence by age 18 in 2017, compared to 8.1% of women in the UK as of 2019.139

Through this picture, it becomes apparent that, despite Trinbagonian independence from British rule and systems, the inherited trauma from violence continues to be passed down and affects the youth and marginalised populations. It is evident there is a need for repair to address the socioeconomic factors contributing to the culture of violence and crime.

Footnotes:

128 Bridget Brereton (1981), A History of Modern Trinidad 1783-1962, Heinemann Educational Books Ltd, Available at: https://archive.org/details/historyofmodernt0000brer , Susan Craig-James (2008), The Changing Society of Tobago, 1838-1938: A Fractured Whole vol.I 1838-1900, Cornerstone Press Ltd

129 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

130 Higman, Slave Populations, pp.67-72

131 See previous reference

132 Brereton, A History of Modern Trinidad

133 “We know that the Trinidad slaves were literally worked to death in this period [from the 1780s to the late 1790s], when they were clearing the forest and establishing new plantations, suffering from gross overwork, primitive conditions and exposure to tropical diseases” Brereton, A History of Modern Trinidad, p.27

134 Please note that indentureship was almost exclusive to Trinidad, the post-Emancipation history is different in Tobago. As Tobago only became British in 1763, the colonial histories, and inherited traumas, are still markedly different. Mangru, ‘An Overview of Indian Indentureship in Guyana, 1838-1917’

135 Central Statistical Office, (2024). “Crime Rate Statistics 2015-2022”. Available at: Crime Rate Statistics 2015-2022

136 World Population Review. (2024) “Murder Rate by Country.” Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/murder-rate-by-country

137 UN, “UN Population Portal- TT”. Available at: UN Population Portal- TT

138 UNICEF, (2021). “Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Trinidad and Tobago”. Available at: UNICEF “Generation Unlimited: the Well-being of Young People in Trinidad and Tobago.

139 UNICEF Data Warehouse, (2017). “Cross-sector Indicators Trinidad and Tobago”. Available at: UNICEF Data Warehouse

Endnotes:

1 Sowell, D. (2004). The Problem of Slavery Studies Today-” How Many? Where? When? and Why: The Numbers Game”. Juniata Voices, 4, 59.

2 Trans-Atlantic slave trade- database. (n.d.). Slavevoyages.org. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

3 Sheridan, R.B. (2009). Doctors and slaves: a medical and demographic history of slavery in the British west indies, 1680-1834. Cambridge University Press.

4 Edward B. Rugemer. (2013). The Development of Mastery and Race in the Comprehensive Slave Codes of the Greater Caribbean during the Seventeenth Century. The William and Mary Quarterly, 70(3), 429–458. doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.3.0429

5 Beckles, H. M. (2013). Britain’s black debt. University of the West Indies Press. https://www.uwipress.com/9789766402686/britains-black-debt/