The King, the Archbishop, and hereditary slavery:

Why the British Monarchy and the Anglican Church (which Charles III heads as its Supreme Governor) must acknowledge transatlantic slavery era harm and engage with descendant communities over reparative justice

By: Desirée Baptiste

March 8, 2024

This article originally appeared on the author’s website and has been republished here with the author’s permission.

“Atlantic slavery rested upon a notion of heritability”, writes Professor Jennifer L. Morgan in her 2018 essay: ‘Partus sequitur ventrem: Law, Race, and Reproduction in Colonial Slavery.’ 1

It worked, therefore, much like British Kingship.

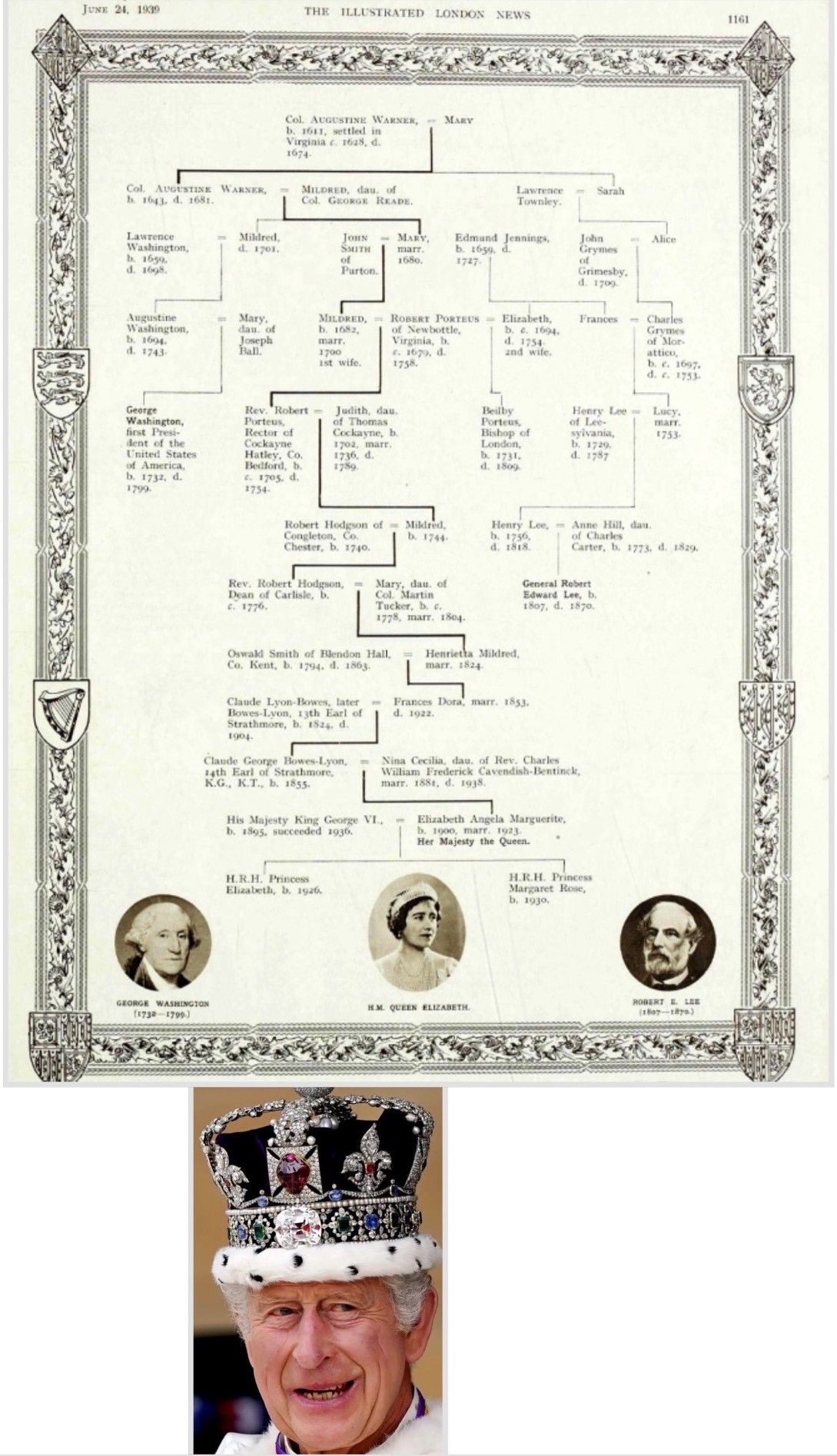

And, interestingly, the “hereditary principle of slavery” (as I refer to it in my 2023 play: Incidents in the Life of an Anglican Slave)2 which rendered chattel slavery in the British Empire a perpetual condition for enslaved Africans and their descendants, is intimately connected to current British Kingship. A direct ancestor of King Charles III (and by extension, also of the heir apparent to the British throne: Prince William) helped to formally entrench the hereditary principle of slavery into Virginia law in 1662.

The ancestor in question: Augustine Warner (1610-1674), a Norfolk-born commoner and the 12-times great grandfather of Charles (via the Queen Mother’s lineage) emigrated to Virginia in 1628, in the decade which saw the sudden explosive commercial success of American tobacco farming: “planters became more adept at tending and curing the leaf”, writes Ian Gateley in La Divina Nicotina, and “the 1620’s turned into boom years, with the best variety fetching prices as high as three shillings a pound.”

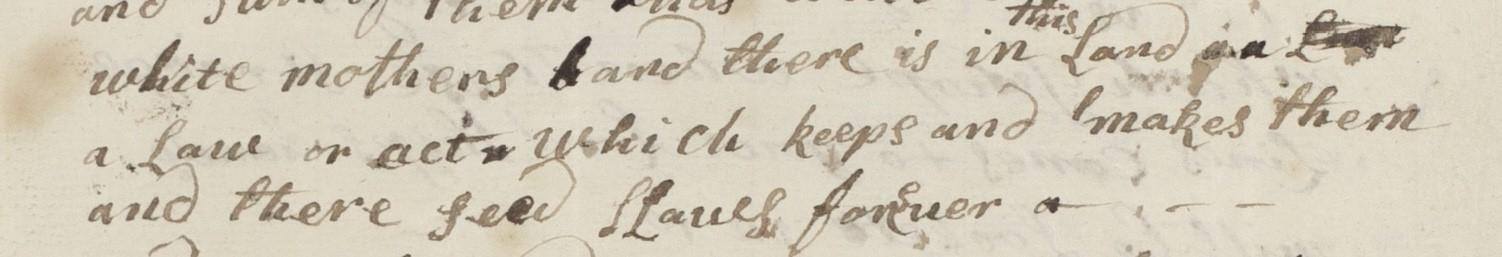

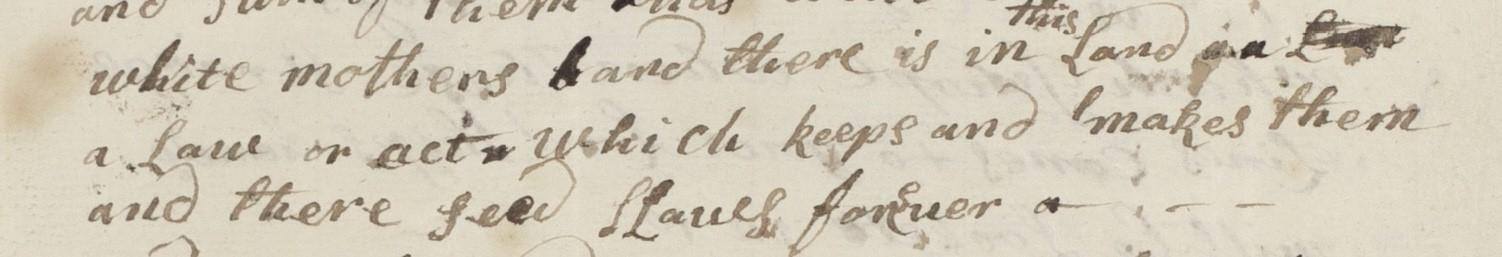

Arriving as an indentured servant (the headright of an earlier settler colonist Adam Thoroughgood)3 Augustine would go on to become a merchant, landowner, tobacco planter and enslaver of Africans, serving in the Governor’s Council from 1660-1671, a period in which at least four key slave laws which Warner approved, as part of the 12-member Upper House, were passed. These include the landmark 1662 Act XII which made the enslavement of Blacks more than just lifelong, but perpetual (by incorporating the ‘Partus sequitur ventrem’ legal doctrine, derived from Roman civil law, and which literally means: “that which is born follows the womb”). Six decades later, in 1723, an extraordinary letter from an anonymous enslaved Virginian mulatto4, asking the archbishop “of London” and King George for release from “cruell bondegg” (this document inspired my 2023 play: Incidents), mentions the legal basis of the inter-generational captivity of the enslaved:

“there is in this Land a Law or act which keeps and makes them and their seed, slaves forever.”

By the time this brave mulatto’s 1723 letter was penned (and no-one knows what happened to him/her after) the various individual slave codes which had accumulated across the 17th century in Virginia had been amalgamated into a single, comprehensive 1705 Virginia Act (“while the various laws establishing slavery would not be pulled together into a full-blown slave code until 1705, laws recognising Black people as slaves were being enacted in Virginia in the 1660’s”).5 It was this 1705 “Law or act” to which the enslaved epistler referred as the source of the “slaves forever” rule, and it had its genesis in 1662 when the hereditary principle was first codified, fully entrenching the racialised slave-system in Virginia by making sure that the condition of the child (whether it should be “held bond or free”) followed the “condition of the mother”, an inversion of English common law where the status of a child followed that of the father. This Act ushered in centuries of additional misery for generations of African Americans who were, from 1662, legally born into slavery. These generations may well have included ancestors of Archie and Lilibet, the King’s own grandchildren! (Meghan’s maternal antecedents were enslaved in Virginia and Georgia).6 “It is quite out of the way,” writes the mulatto in 1723, referring to the fact that, as he/she puts it: “I am my brother’s slave”. A consequence of the 1662 law and its 1705 update was that mulatto children fathered by a white slaveowner with an enslaved African woman could end up bequeathed in wills as property to the slaveowner’s relatives, which is likely how the mulatto epistler ended up enslaved by his/her own brother. The Act was a deliberate “innovation”, writes William M. Wiecek, one that “was made necessary by the fact that many children of slave mothers had white fathers:” and that “to permit these mulatto offspring to take the status of their father would not only be an anomaly (a slave woman raising her children to freedom presented obvious difficulties) but it would also lead to an unthinkable blurring of racial and social lines in a society that viewed miscegenation as a stain and contamination.”7 Also, the mulatto child represented an increase in the master’s property if declared a slave.

“Quite out of the way”, indeed!

But worse things happen at sea, as they say (and they certainly did, back then!)

For example, King James II (1633-1701), who invested in the Royal African Company of England (he was also its Governor from 1660-1668), oversaw an institution which “shipped more enslaved African women, men, and children to the Americas than any other single institution during the entire period of the transatlantic slave trade” according to William Pettigrew8 (from 1672 to the early 1720s, the RAC transported some 150,000 enslaved Africans, mostly to the British Caribbean).

Other royal personages are known to be connected to transatlantic slavery, on an institutional level (i.e. in their role as head of state) such as King Charles II (1630-1685), brother and predecessor-in-office of James II. But perhaps lesser known are the family connections of the current King to chattel slavery, such as his ancestor Edward Porteus who owned slaves in Virginia, including a “Negroe girl Cumbo” left in his 1700 will (my play brings this family story to light, as was reported in The Guardian in April 2023)9. As well as the fact that, at the same time that the 1663 Charter signed by Charles II gave official State sanction to the Company of Royal Adventurers into Africa (which became the Royal African Company after 1671) to trade in, not just “gold, redwood and elephants’ teeth” but “negroes”, an actual ancestor of Charles III (which Charles II isn’t, though he is an ancestor of William and Harry via Princess Diana’s lineage) was co-crafting arguably the most critical legal blow to the status of the African American in the history of British chattel slavery. “Virginia was the first colony to regulate maternal descent”, explains Professor Morgan who has written widely on the importance of the 1662 Act in “crafting racial inheritance through enslaved women.”10 And as William J. Wood wrote, in a 1970 article: The Illegal Beginning of American Negro Slavery: “In the case of Virginia, the fate of the Negro was sealed as total chattel slavery by 1662, forty-three years after the arrival of the first Negroes in Jamestown.”

The British royal family’s ancestor helped to create, to quote Jennifer L. Morgan:

“An economic and moral environment in which the appropriation of a woman’s children as well as her childbearing potential became rational, and indeed, natural.”11 So natural, that Thomas Jefferson (whose contemporary, George Washington, was Augustine Warner’s great great grandson) could write this, about the enslaved woman. She:

“who brings a child every two years (is) more profitable than the best man of the farm, what she produces is an addition to the capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption.”12

In creating the play: Incidents, drawing on the fragments of biography contained in the 1723 letter in order to give the brave enslaved Virginian epistler, via art, as full a life story as possible (a form of repair), a key decision I made: to make the protagonist female, came from a desire to explore the female experience of chattel slavery, including the hereditary principle, as well as from a recognition of the fact that, as Professor Verene Shepherd13 of the University of the West Indies has pointed out, the burden of chattel slavery fell hardest on the Black woman. Professor Shepherd, speaking to the Repair Campaign recently, explained:

“We have to admit that chattel enslavement and the burden of production fell disproportionately on women and therefore I want to see and I want to help to shape the review of the (Ten Point) plan to ensure that that fact is there and that there is a specific demand for reparatory justice for what happened to women…because we continue as women to experience the legacy of the discrimination that colonialism brought and left here in our region.”14

I am also finding that, from the scholarly research that went into building the play: Incidents, there might be a case for the royal family to answer, in relation to Caribbean reparations, for the Virginia “hereditary” story. As Sir Hilary Beckles stated in February 2016 (at a Harvard Law School event: ‘On Reparatory Justice for Global Development’) reparations is an agenda led by Caribbean governments and other organisations (including CARICOM) which speaks as much for the North American experience as for the Caribbean.

Here are some of the other death blows to Black humanity that the King’s ancestor Augustine Warner helped to deliver:

1661: An Act which allowed any free person the right to own slaves

1667: An Act which declared that the conferring of baptism “does not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom.”

1669: An Act declaring that “if any slave resists his master (or other by his master’s order correcting him) and by the extremity of the correction should chance to die, that his death shall not be accounted a felony.”

To sum up that decade’s death blows: “Slavery was for life and in perpetuity: children born to a slave were simultaneously born to enslavement; Christians might be slaves; and slaves might be beaten to death with impunity.”15 By the end of the decade which was “committed to unrestrained enslavement” under Augustine Warner’s watch: “Virginia had also committed itself to the quantum of terror that sustaining the institution required.”16

The hereditary principle of slavery and the caribbean

The British Caribbean colonies, too, created a slavery regime, and Virginia’s laws of the 1660’s may well have been influenced by the islands, where, for example, a comprehensive Barbados Slave Code of 1661 was passed: An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes. “Barbadian transplants influenced the development of slave regimes in each of slavery’s three mainland centers”17 in North America, including Virginia, writes Christopher Tomlins (Carolina and the mid-Atlantic are the other two). “In the case of Virginia, Barbadian trading links created channels of communication that introduced migrating planters and elements of Barbadian slave law to the Chesapeake” and the island was indeed “a principal source of the Caribbean slaves who likely constituted the larger element in the mainland’s initial slave population.”18 (Virginia’s acting governor in 1708, Edmund Jennings, wrote that before 1680 “what negros were brought to Virginia were imported generally from Barbados for it was very rare to have a Negro ship come to this Country directly from Africa”).19

In Barbados, the heritability of African enslavement was a fact from the colony’s start, as is clear “in estate inventories from the 1640’s and 1650’s.”20 Professor Jennifer L. Morgan tells me that “from the beginning, Barbadian slaveowners understood that they had the right to harness enslaved women’s reproductive potential to enrich themselves and their own children” and that “with growing frequency they referred to the future ‘increase’ of the women they enslaved when writing their wills—promising unborn children to their widows, sons, and daughters.”21

The hereditary principle of slavery as it relates to the Caribbean is one of the chattel enslavement dynamics that the Caribbean nations and other organisations currently drafting reparative justice claims against the UK might wish to consider more closely. The hereditary principle of slavery was practiced as far back as the 1640’s, acted out on plantations through the cruel use of child labour from an early age and enacted through courts (probate hearings where wills were settled, bear this out), and observed too, in the travel writings of the age:

“In 1654 John Berkenhead wrote that Barbadians killed their slaves with impunity and ranked them with ‘doggs.’ Henry Whistler described a multi-ethnic servant population of ‘English, French, Duch, Scotes, Irish’ and Spanish Jews, along with the ‘miserabell Negors borne to perpetuall slavery thay and Thayer seed.’ Whistler’s remarks indicate the Barbadian adoption of hereditary slavery as well as a broad catchment region for European indentured servants. The council in 1636 had not described slavery as hereditary”22 , but had stated that all “negroes and indians” brought to the island to be sold should serve for life.23

The evolution by the 1650’s, to the practice of hereditary slavery, was being pragmatically worked out by the English through law and custom (some scholars have suggested the English simply copied Iberian Empire practices which emulated ancient Greece and Rome, but this seems superficial, as it doesn’t account for the fact that the English were developing chattel slavery’s scaffolding by degrees since slaves first began appearing on the island in the 1630’s).

Which means that for nearly 200 years Black and mixed-race children born in the British Caribbean territories were enslaved from birth. And since the Church of England profited from the labour of children born on the Codrington Estate in Barbados (owned and run by the Church’s missionary arm: the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts whose President throughout the slavery era was always the Archbishop of Canterbury) the Anglican Church too needs to be identified by Caribbean nations claiming reparative justice, for a centuries-long crime against the humanity of Black mothers and their children who were forcibly held captive from the moment they exited the womb. In a scene from my play: Incidents, the protagonist, deported to Barbados, witnesses, on the Codrington Estate: “small children on the plantation floor/And not just weeding, but doing a whole lot more”

This verse is based on a detail in the archives at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University (the USPG, formerly SPG’s papers are deposited there) which points to four dozen special sized agricultural hoes “Very small for children” which were shipped to the Codrington Estate from Britain in 1756, for the labour of Black and mixed race children to be harnessed by the Anglican establishment.24

“Suffer little children…to come unto me” said Jesus. “Am I my brother’s keeper?”, says the Holy Bible, which is a long way off from the Virginian’s: “I am my brother’s slave.”

“The hereditary principle of slavery was born

A principle lodged in the Black woman’s womb

Like my mother’s, and we’ll come to her soon

Yes, all Black mothers had their sacred wombs

Transformed into somethin’ like prisoners’ tombs”

(‘Incidents in the Life of an Anglican Slave’, 2023)

Endnotes:

- Small Axe, Volume 22, Number 1, March 2018, No. 55, pp. 1-17 And: https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/abolition1313/files/2020/08/Morgan-Partus-1.pdf

- https://www.instagram.com/p/C3iNiYOg0Qs/?igsh=aW90NmF5Z2ZvcHB0

- A colonist could obtain fifty additional acres by paying for another colonist’s passage. Often this new immigrant became an indentured servant, usually for seven years, to the colonist who paid his ship fare.

- Mulatto: “person of mixed white and black ancestry, especially a person with one white and one black parent.” Oxford Online Dictionary.

- Darold D. Wax. ‘Preferences for Slaves in Colonial America.’ The Journal of Negro History. Vol.58, No.4, October 1973. Published By: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 371-401, p.372

- https://original.newsbreak.com/@cheryl-e-preston-1594046/2989087477913-meghan-markle-s-mother-doria-ragland-has-ancestors-who-once-lived-in-virginia

- William M. Wiecek. ‘The Statutory Law of Slavery and Race in the Thirteen Mainland Colonies of British America’. The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol 34, No 2, April 1977, pp. 258-280, p.263

- William Pettigrew. ‘Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752’. University of North Carolina Press, 2013, p.11

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/apr/27/direct-ancestors-of-king-charles-owned-slave-plantations-documents-reveal

- Jennifer L. Morgan. ‘Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery.’ University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, p.67

- Ibid, p.7

- Ibid, p.92

- Director of the Institute for Gender & Development Studies from 2012-2017 at the UWI, Mona Jamaica

- https://www.instagram.com/reel/Cz4qL_ZvAjQ/?igsh=MW9pcG5yemhvazZ3Mw%3D%3D

- Christopher Tomlins. ‘Freedom Bound: Law, Labour, and Civic Identity in Colonizing English America, 1580-1865’. Cambridge University Press, 2010, p.463

- Ibid, p.463

- Ibid, p.431

- Ibid, p.452

- Christopher Tomlins. ‘Freedom Bound: Law, Labour, and Civic Identity in Colonizing English America, 1580-1865’. Cambridge University Press, 2010, p.452

- Ibid, p.420

- Professor Jennifer L. Morgan to Desirée Baptiste by email, 7th March 2024

- Edward B. Rugemer. ‘The Development of Mastery and Race in the Comprehensive Slave Codes of the Greater Caribbean during the Seventeenth Century.’ The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol.70, No.3, July 2013, pp. 429-458, p. 434

- John C. Coombs. ‘Others Not Christians in the Service of the English.’ The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol.127, No. 3 (2019), pp. 212-238, p.214

- Bodleian Library at Oxford University. Special Collections. SPG-L. ‘Invoice of goods to be sent from England to Barbados’. January 12, 1756. B6/63