Towards Inclusive Reparatory Justice: Indian Indenture and the Guyana Experience

By: Baytoram Ramharack

December 19, 2023

About the Author

In August 2023, Charles Gladstone, a descendant of a former British plantation owner, traveled to Guyana with five relatives to offer a formal public apology for chattel slavery. Charles Gladstone told his audience at the University of Guyana that “we acknowledge slavery’s continuing impact on the daily lives of many” and he pledged to support a fund for various projects to be established in Guyana as part of a “long-term relationship” between his family and the people of Guyana. Charles also apologised for his ancestor’s role in “bringing indentured labourers to Guyana.”

This visit was a historical turning point for Guyanese – and the Gladstones. For one, it meant that the Reparations movement in the Caribbean, initiated largely by Professor Hilary Beckles, the Chairman of CARICOM Reparations Commission, and Professor Verene Shepherd, Director of the Centre for Reparation Research at the University of the West Indies, has produced tangible results based on the Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice provided by the CARICOM Reparations Commission (CRC). Two, the visit by the Gladstones established an important precedent for other European families whose generational wealth was gained from enslaved and indentured labour.

The Gladstones’ visit was particularly important because Sir John Gladstone (1764-1851) was the most influential plantation owner, trader and politician responsible for the introduction of Girmitiyas (indentured Indians) in the Caribbean. Gladstone, a Scottish planter who amassed a fortune by trading in corn and cotton with the United States and Brazil, maintained significant influence in the British Parliament (he was the father of William Gladstone, four-time Prime Minister of Britain). By 1826, at age 62, he owned the Vreed-en-Hoop estate, one of the largest sugar plantations in Demerara. FM Gillanders (of Gillanders, Arbuthnot, and Company), the firm that brokered Gladstone’s plan to send Indian immigrants to British Guiana, was a nephew of Gladstone’s wife.

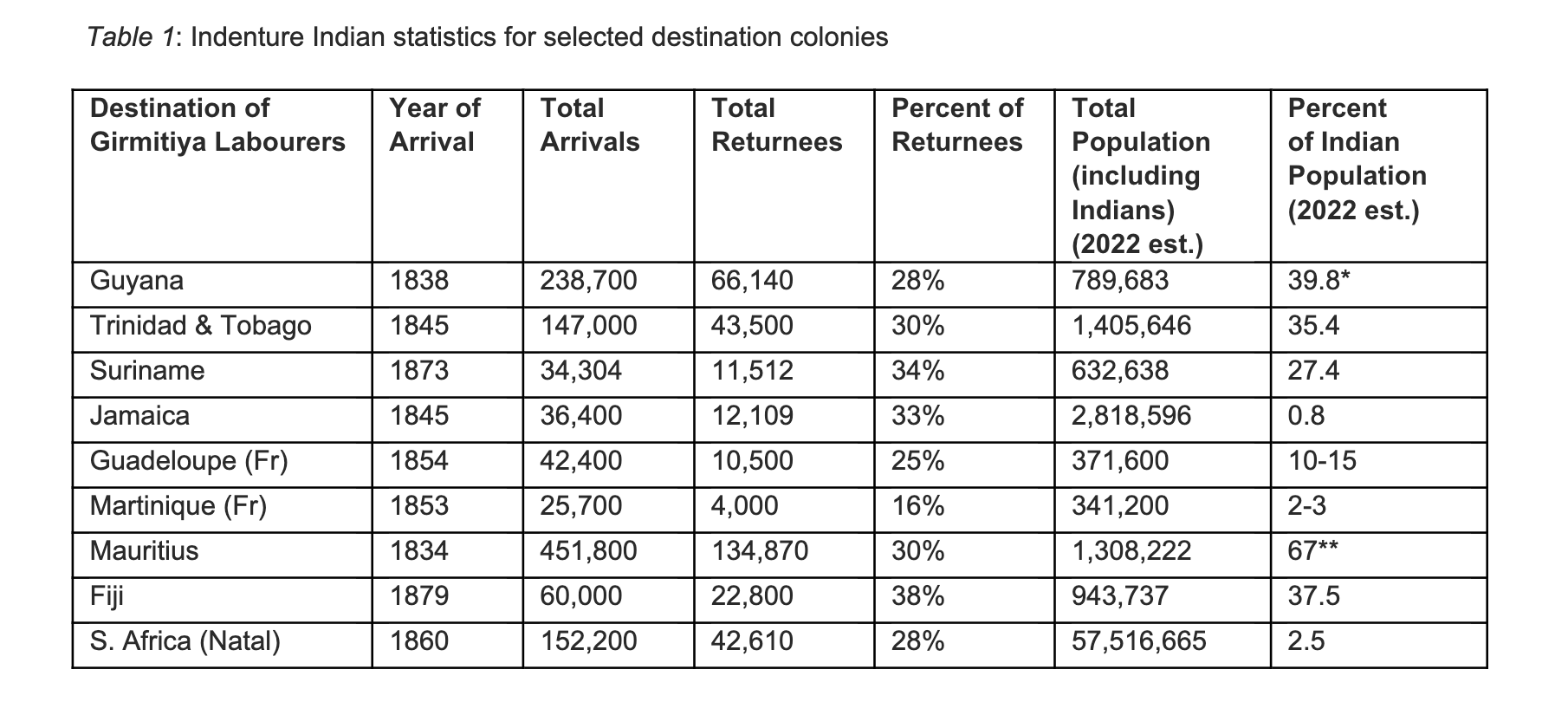

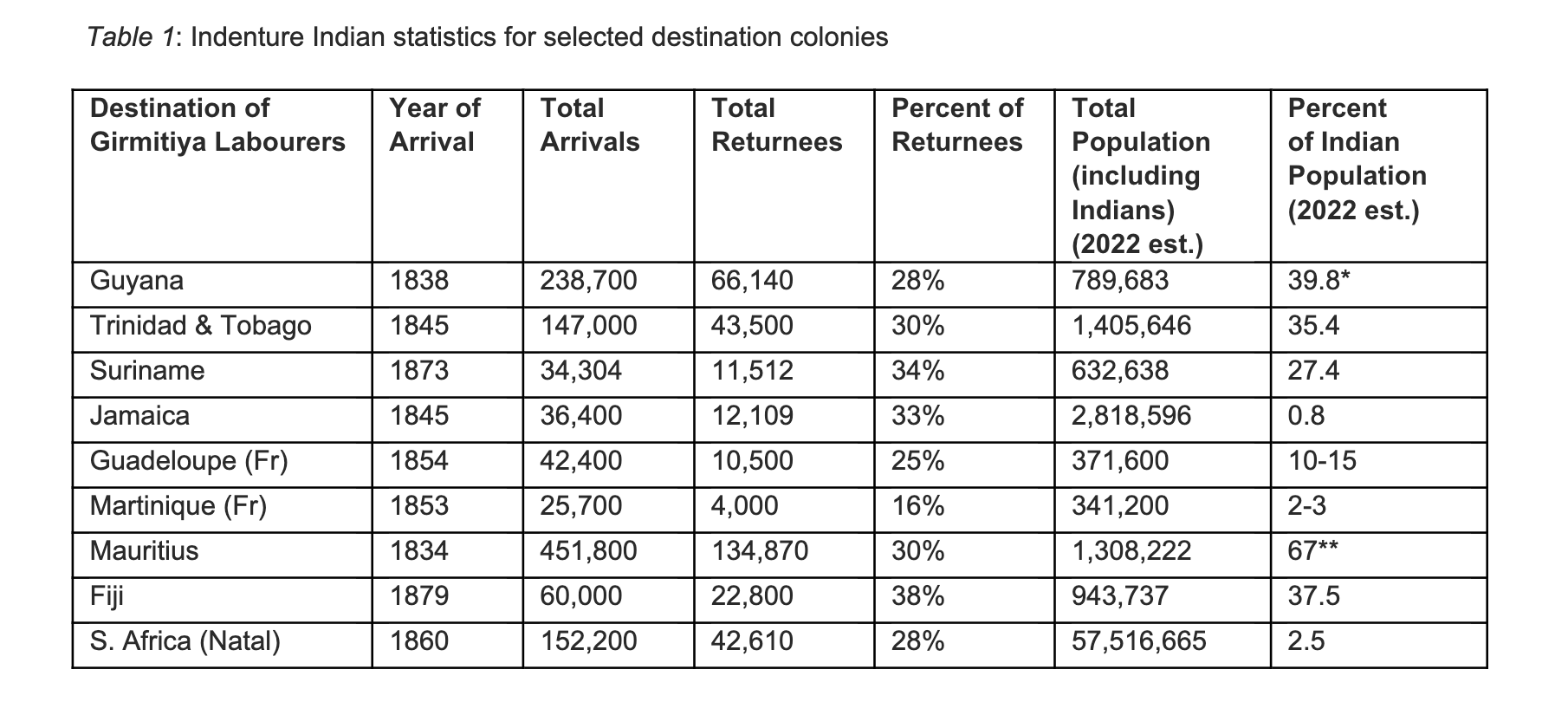

To buttress his case for the introduction of “bound coolie” labourers in the Caribbean, Gladstone unhesitatingly reminded the Kolkata brokerage firm in India’s West Bengal state of the existence of an already successful scheme of supplying Indian labourers to work on the island colony of Mauritius since 1834. Thus began the transportation of Girmitiyas to British Guiana in 1838. The first two ships transporting Indian labourers to the Caribbean, the SS Hesperus and the SS Whitby, arrived in British Guiana in 1838, ironically, on the same day (May 5), three months after sailing at sea. Table 1 below shows the disparity in the number of Indians taken to various colonial holdings in the Caribbean.

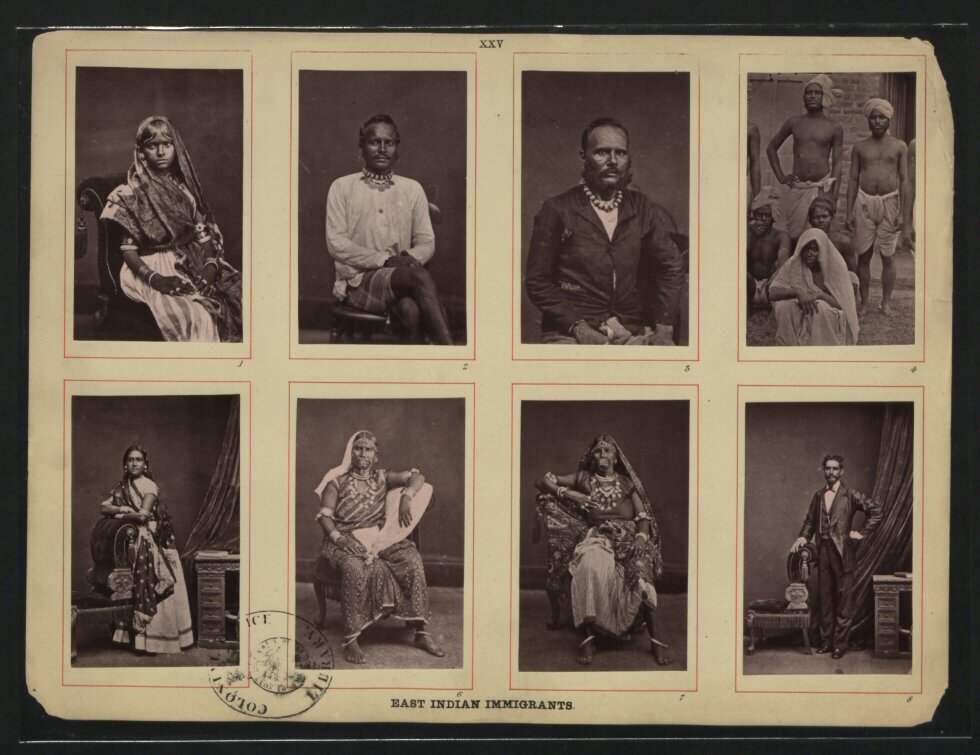

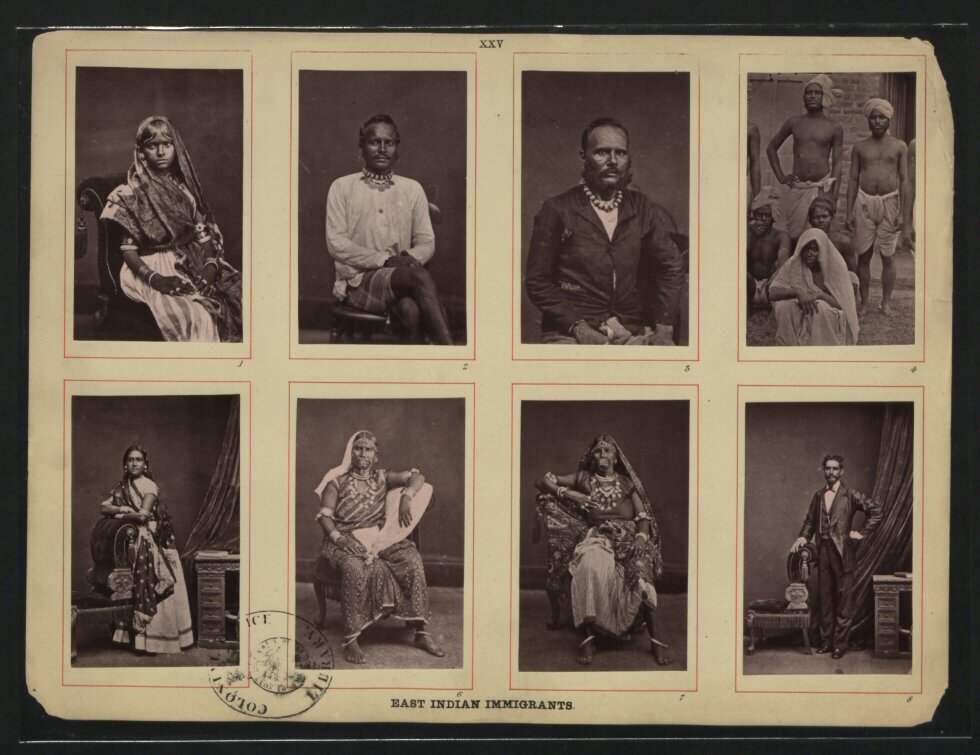

The history of Indian indenture, whether under voluntary or non-voluntary conditions, commenced with the trans-shipment of thousands of Girmitiyas from British India to colonies worldwide. An estimated 543,914 to 750,000 Girmitiyas were brought to the Caribbean as indentured labourers from 1838 to 1917. In Guyana, about 238,700 Indian immigrants came from India, 147,000 were taken to Trinidad and Tobago, and 34,304 were taken to Suriname (under Dutch control). These three Caribbean countries, including Jamaica, have large Indian populations today. Well over a million Indians now reside in the Caribbean, representing at least 20 percent of the region’s population.

The kala pani crossing (Indian and Atlantic Oceans) would have been a very traumatic experience for the Indian immigrants, especially for the early batch of Girmitiyas, who spent much more time on the immigrant ships before reaching their respective colonial destinations. The ship’s odyssey was followed by the plantation experience, reminiscent of conditions that approximated those of chattel slavery, leading Joseph Beaumont, Chief Justice of British Guiana (1863 to 1868), to describe indentureship as The New Slavery. What is unique about Indian indenture in Guyana was that this British Colony experienced much more widespread plantation riots and rebellions compared to all other diasporic colonial holdings where Indians were taken – a testimony to its oppressiveness.

The Gladstones recognised the exploitation and abuse associated with the oppressive and coercive indenture system (which also included Portuguese and Chinese immigrants). Guyana’s President Irfaan Ali made it clear that he supported reparations for both chattel slavery and indentured labourers. His administration is supportive of the Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice provided by the CARICOM Reparations Commission (CRC). Indians support the plan because all or most of the points of the plan are inclusive of the indenture experience in Guyana, and the Caribbean. For example, research has shown that issues like alcohol abuse, suicide and gendered violence are directly related to the Girmitiya experience, and these social issues fall within the parameters of the plan that calls for “Remedying the Public Health Crisis.” Yet, nowhere in the Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice is there any mention of the indenture experience in the Caribbean.

Verene Shepherd has pledged that the Centre for Reparation Research, of which she is the Director, will work to ensure that the CARICOM Reparations Commission take into consideration the indenture experience as a matter that should be integrally represented in the plan. By doing so, the 2014 Ten-Point Plan for reparatory justice will be more representative, and inclusive of the unique experiences of the peoples of the Caribbean. It is incumbent upon the leaders of the movement for reparatory justice to amplify the voice of all individuals for whom justice is long overdue.

Author’s notes:

* This is the percentage of Indians in Guyana as per the 2012 census.

** Mauritius has not compiled data by race/ethnicity since 1972.

Note also that Indians (about two-thirds of whom were Hindus) made up most of the Girmitiya population in these countries. Population figures represent close estimates.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica (2022); The World Factbook, 2022 (US Central Intelligence Agency). Several other sources were utilised for information, including Birbalsingh, Frank, ed. (1989), Indenture and Exile: The Indo-Caribbean Experience. Toronto: Tsar, p. 9; Hardeen, Devi, ‘The Brown Atlantic: Re-thinking Post-Slavery’, Black Atlantic Resource Debate, University of Liverpool, pp. 1-22, https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/csis/blackatlantic/BARD-Essay-1-1.pdf; Laurence, K.O. A question of labour: indentured immigration into Trinidad and British Guiana, 1875-1917. London: James Currey Publishers, 1994; Mansingh, L. & A. Mansingh. Home away from home, 150 Years of Indian Presence in Jamaica 1945-1995. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 1999; van Lier, R.A.J. (1971), Frontier Society: a social analysis of the history of Surinam. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoof; Nath, Dwarka. (1950), A History of Indians in Guyana. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons; Northrup, David. (2000), ‘Indentured Indians in the French Antilles. Les immigrants indiens engagés aux Antilles françaises’, Revue d’histoire, pp. 245-71; Northrop, David (1995), Indentured Labour in the Age of Imperialism, 1834-1922. Studies in Comparative World History. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 53; Roopnarine, Lomarsh. (2006), Indo-Caribbean Indenture: Resistance and Accommodation, 1838–1920. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, p. 6, and Shepherd, V.A. Transients to settlers; the experience of Indians in Jamaica, 1845-1950. Leeds: Peepal Tree, 1992.