The Caribbean Church and the Reparations Movement

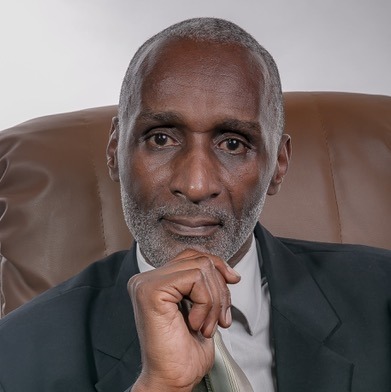

By: Rev. Ronald A. Nathan

January 29, 2024

“A lot of people don’t like to have this conversation, but the time has come for it,” so said the honourable Edmund Hinkson Member of Parliament for St. James East to the Barbados parliament in December 2023 as insisted that the Church of England and the British government should pay reparations to the country.

He was taking his cue from the Barbados Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley who recently revealed that “Barbados was owed $4.9tn (£3.9tn) by slave-owning nations.”

These statements came considering the Church Commissioners of the Church of England admitting that its benefactor, the Queen Anne’s Bounty, traded enslaved Africans. The commissioners committed themselves to pay US$122 million to the descendants of those who were affected so they would have a better and fairer future.

Later, another Church of England’s agency, the United Partners in the Gospel (USPG) in September 2023 offered £7 million (US$8.8m) to Barbados for its role in the slavery and its ownership of the slave plantation Codrington Estate.

With the flurry of activity that has taken place in the last few years concerning reparations within the Caribbean, United Kingdom, and the United States of America and even in Africa, why has the Caribbean Christian Church been so reluctant and slow to engage the issue of reparatory justice?

I want to suggest that this reluctance and hesitancy are due to historical and theological factors.

The arrival of Western European Christianity in the Caribbean was simultaneous with European expansionism into the so-called New World. Western European Christianity gave philosophical, theological, psychological, political, social, and cultural succour to the whole European colonial enterprise. Supplementary to Christopher Columbus’s first journeys to the region 12 missionaries from Spain landed on the island of Hispaniola, now known as the Dominican Republic and Haiti in 1494.

The Christian Church in the Caribbean was heavily vested in the colonies and their plantation economies. The diversity of the Christian Church was reflected in the Caribbean in the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant Church denominations. They sent their representatives to provide spiritual support, engage in evangelism, missions, and service as part of their biblical mandate and fulfil their colonial patriotic duty.

Carmen Curley of Miami University states, “because slavery was such a lucrative business, many in the church continued to profit from the despicable institution.” Christopher L. Brown, examining the historical British context of the 16th 17th and 18th centuries declared that,

“… to the many with an investment in the colonial economy or concerned about Britain’s standing among European rivals, an Empire without slavery was simply unthinkable.”

The theological machinations that took place to allow for the subjugation of the Christian ideal ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you,’ and the idolisation of wealth was framed and justified as a Christian ‘missions imperative.’ The indigenous peoples of the Caribbean became barbaric and Africans inferior, primitive and followers of witchcraft. Both groups were therefore considered in need of European civilisation, Christianisation, and commercialisation.

The present commitment of the Caribbean Christian Church to the biblical concept of righteousness and justice requires that all Christian clergy and laity irrespective of denominational membership, theological heritage, ideological identification, or political affiliation contribute to the call for reparatory justice.

Reparatory justice is an acknowledgement and admittance that emancipation in and of itself did not address fully the deep injury inflicted on the indigenous peoples of the region, and the prolonged enslavement of Africans. It recognises that there is unfinished business in the ongoing psychological, economic, social, and theological consequences facilitated by the colonial enterprise.

The Christian in the Caribbean cannot be exempt from these discussions notwithstanding the fact remains that there is a tradition of reparatory justice found in the biblical texts. The moral and ethical arguments are substantial and calls on the Christian Church to engage truthfully and humbly. How can it be morally right for European nations to compensate the enslaver and not the enslaved? How is it morally right for European nations to be enlarged, empowered, and enriched over the centuries by the ill-gotten gains of enslavement? How can it be that the enslaved territories can then be positioned to be ever dependent and impoverished in the service of the empowered?

What is sad is that despite the work of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the national reparation committees established in each of the CARICOM member countries, many Christians in the Caribbean are almost totally ignorant of the argument for reparations. Two views are prominent even here in Barbados ‘this has nothing to with me’ and ‘let sleeping dogs lie.’

These views reflect the unwillingness by the Christian Church in the Caribbean to critique the roots of their theologies, philosophies, emphases, and methodologies. This leads us to inadvertently support a status quo that is premised on colonial and neo-colonial objectives and therefore doing harm to the very people we serve.

Noel Leo Erskine, one of our esteemed theologians puts it like this, “The colonisation of so called ‘developing areas’ is complete when theology and religion are imported to justify and, in effect, legitimise racial superiority and economic domination.”

The Christian Church in the Caribbean, in seeking its own authentic voice, must develop a postcolonial theological critique that questions Western European structures of power, dominant systems, and embedded ideologies in our region and suggest social transformations that recognise and validate the perspectives of our marginalised peoples, cultures, and identities. Our unwillingness or reluctance to do so points to a lack of ecclesiastical and theological leadership and our failure to incarnate the gospel into the Caribbean body politic.

In Trinidad and Tobago there is a saying “Yuh cyah play mas if yuh ‘fraid powder.” The Christian Church in the Caribbean cannot wish on one hand, to ‘speak truth to power’ and on the other hand, be unwilling to address the power structures of colonial oppression and its present neo-colonial iterations. There are “sacrifices necessary for liberation” until we are willing to face these difficult reparatory discussions we will be continually talking about ‘emancipation soon come.’

The desire for reparatory justice is one such task in redeeming our times. The persistent poverty George Beckford alluded to in 1972 is the legacy of a colonial system that has placed a noose around the necks of the Caribbean peoples for generations. Our faith commitment requires us to repent of the sins of our forefathers and to make restitution including ‘repairing the breach’ that normalised and institutionalised intergenerational oppression.

The formation of the Churches’ Reparations Action Forum (CRAF) in Jamaica in 2019 was necessary and a move in the right direction. Its objective to provide opportunities for collaboration between like-minded Christians across the Caribbean is indeed critical. Courage is required by all in the historical analysis and theological task involved in the demand for reparatory justice.

About the author:

Ronald A. Nathan is an elder of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Barbados. He is a public theologian, author, writer on Pan-African affairs, and the world politics editor of the Star of Zion newspaper.