Repairing the Legacies of Indentureship in the Caribbean

A conversation with Professor David Dabydeen

The Repair Campaign interviewed Professor David Dabydeen, Director of The Ameena Gafoor Institute for the Study of Indentureship and its Legacies.

December 19, 2023

In 1838, the first ship of indentured servants from India arrived in British Guiana. What were the factors that led to this?

In the 1830s, it was almost certain that the enslavement of Africans would end. When it ended in 1834, plantation owners – especially Sir John Gladstone – thought, “well, what would I do now? Where would I get a labour force? They’ll start wanting wages, my God.”

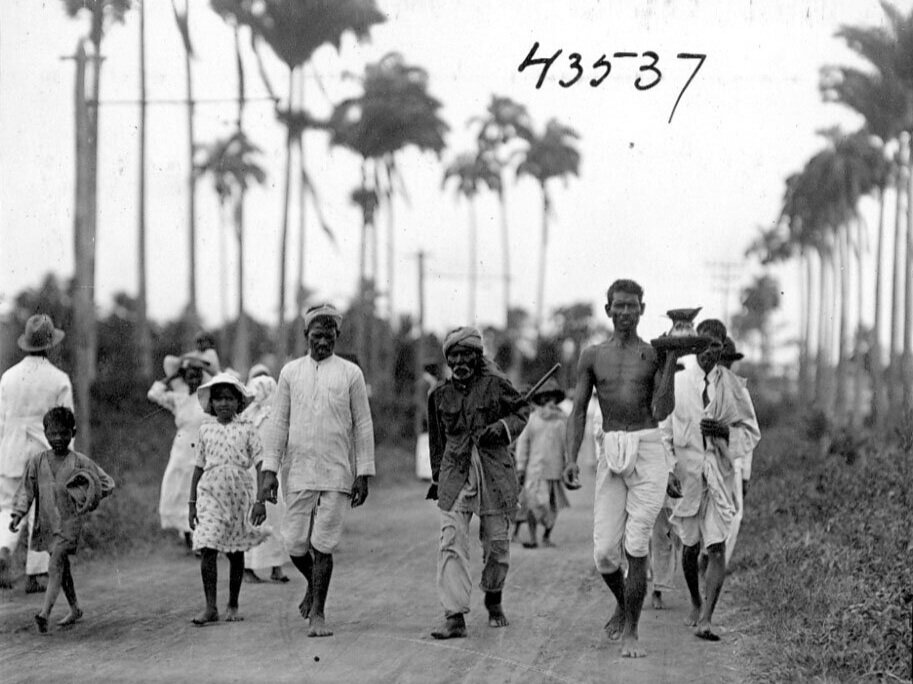

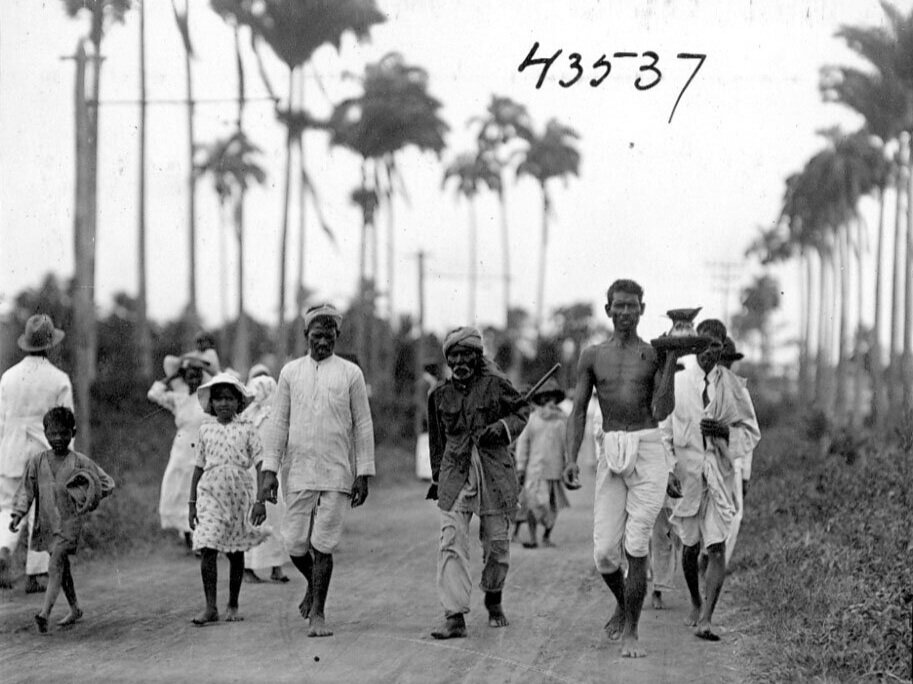

As a result, Gladstone organised for the trafficking of Indians to British Guiana. It was mostly men to begin with and, in 1838, 396 ‘Gladstone coolies’ arrived. Over a period of time, about half a million arrived altogether – about a quarter of a million arrived in British Guiana alone and another 150,000 in Trinidad.

The Indians were shipped over to replace black labour on the sugar plantations and to stop African aspirations, not just for economic benefits and economic progress but also for political and social progress. The Africans were quite willing to work as free men and free women but they wanted several things: proper wages, to make sure their children didn’t have to work, that there was basic schooling, that there was no oppression and that there was no violence against their settled communities. The freed Africans started setting up their villages and political communities as an alternative source of power which, of course, was a threat so the planters wanted to stop all of that.

Based on your research and historical evidence available, can you describe what life was like for an indentured labourer?

When the Indians first arrived in say British Guiana, the first thing was absolute surprise. They were meeting Africans for the first time, they didn’t know about chattel slavery, they didn’t know where they were going – they didn’t even know it was across the oceans.

Although conditions in India were no better in many ways than in the plantations in Guyana – remember that the Indians were oppressed by caste, there were regular famines, diseases and all kinds of other tribulations – the plantation life was deeply uncomfortable, if I can use an understatement.

First of all, they were far from home and there is a sense of loss that comes with that. They also occupied the same shacks that were recently vacated by the enslaved Africans which were not fit for animals, never mind human beings. They had to work 12 hours a day and were regularly beaten as the enslaved Africans were, with wages deducted for every minor misdemeanour.

How was Indian indentureship similar or different to chattel enslavement?

The condition of Indian indentured labourers was similar but very different from that of the enslaved Africans. For a start, Indian indentured labourers were not property. They couldn’t be bought and sold as the African enslaved people were. They were also given a return passage after five years if they wished it. And, on paper at least, there was somebody called the ‘Protector of Immigrants’. The African enslaved didn’t have that.

On the other hand, the enslaved Africans had no chance of return. And the plantocracy attempted a great degree of cultural genocide which means wiping out all traces of African-ness, whether by banning drumming, music, oral poetry or food. That attempt to wipe out African-ness did not obtain with the Indians. While the missionaries tried their very best to convert the Indians to Christianity – and many of them were converted – many of them resisted and they were able to resist without being beaten or oppressed.

However, a lot of the rights that the Indian indentured labourers had on paper were exactly that, on paper, and were hardly practised. The Indian indentured labourers suffered a similar kind of humiliation and physical beatings as enslaved Africans, maybe not to the same extent, but there it was. Just because chattel slavery ended in 1838 doesn’t mean the plantocracy changed their ethics and their habits. They didn’t put down the whip and say, “oh dear, we have to treat these new workers with respect.” They continued their old habits of coercion.

The Ameena Gafoor Institute, of which you are director, researches indentureship and its legacies. What are the historical and inter-generational trauma and legacies of Indian indentureship and how do they impact today’s society?

The relationship between historical and contemporary experience is very complex. I will only point to two aspects of how contemporary society has been affected by the past. First of all, Guyana was underdeveloped, we were turned into one big sugar plantation. In the 18th and 19th century, we lived in sugar cane. When you’re hungry you eat the sugar cane and sometimes that’s all you had to eat. As a result of this, we have diabetes and hypertension up to today. In the case of Indian indentureship, that’s a direct result of those experiences.

Secondly, I would definitely say in my own belief that male violence against women is a result of the sex ratio imbalance on the plantations because the ships that brought Indians brought very few women. And then, the plantation experience really was about beating – people being beaten to work, beaten to come home from school, beaten for any small misdemeanour.

And we know from the historical records that an Indian woman married to an Indian man can’t even look at another Indian man. She can’t even speak to another Indian man without the threat of violence from her husband. So I’m convinced that one of the legacies of indentureship is physical violence against women.

It seems to me that kind of violence against the body, in this case against women, has been sustained over centuries. Although I’m not a Sociologist or Anthropologist, in my limited experience, I would have to argue that this is an inherited practice because of chattel slavery and indentureship.

Indentured labour is not mentioned in the 2014 10-point plan but the CRC intends to revise this to include indentureship. How would you like to see indentureship represented in such a revision?

Whenever you mention chattel slavery, put a comma and add indentureship. That’s all. Slavery and indentureship. Let us be together. You could not have indentureship without chattel slavery. The two are intimately entwined. They’re different in their form of unfree labour but they’re historically entwined.

Let us present a united front: chattel slavery and indentureship, women and indigenous people. However you put it, involve all of us. We were all in the same boat, but we all suffered differently. Liam Kennedy, the Irish historian, talks about the ‘MOPE syndrome’ – the Most Oppressed People Ever syndrome. I’m not into a calculus of suffering. I know and have read about the absolute brutality endured by enslaved Africans. Indians were beaten a different way and Indians were beaten for different reasons.

We’ve inherited policies and practices of divide and rule that the great Walter Rodney talked about explicitly in a beautiful essay he wrote called “Plantation Societies,” where he said at the very beginning of the encounter between Indians and Africans, there was the motive of dividing them. Just three years after slavery ended, in 1841, the Africans went on strike because they wanted better conditions and better wages, normal human demands. And you know what? They won. The plantocracy had to give them what they wanted, more or less.

A few years later, they went on strike again, because their wages were being cut by 25%. But by that time, the plantocracy had shipped in over 6,000 Indians, who then broke the strike, because they were put to work. They had no choice in being put to work. They couldn’t say no.

And that was the beginning of the divide and rule that still afflicts us today. Therefore, when we’re talking about indentureship and reparations, let us all be in the same boat and present a united front rather than the division, antagonism and measuring our suffering against each other that we’ve inherited.

I think that we need unity or we’re much weaker. If you have unity, it does not mean you diminish each other. It means you recognise the particularities of African suffering and tribulation, which are horrific, and you know what the Indians went through as well, which is less in terms of the kinds of humiliations and objectification that the Africans endured. Nevertheless, empathy is very important today in Guyana. If we’re to talk about bridging the divides, we have to recognise we’re in the same boat.

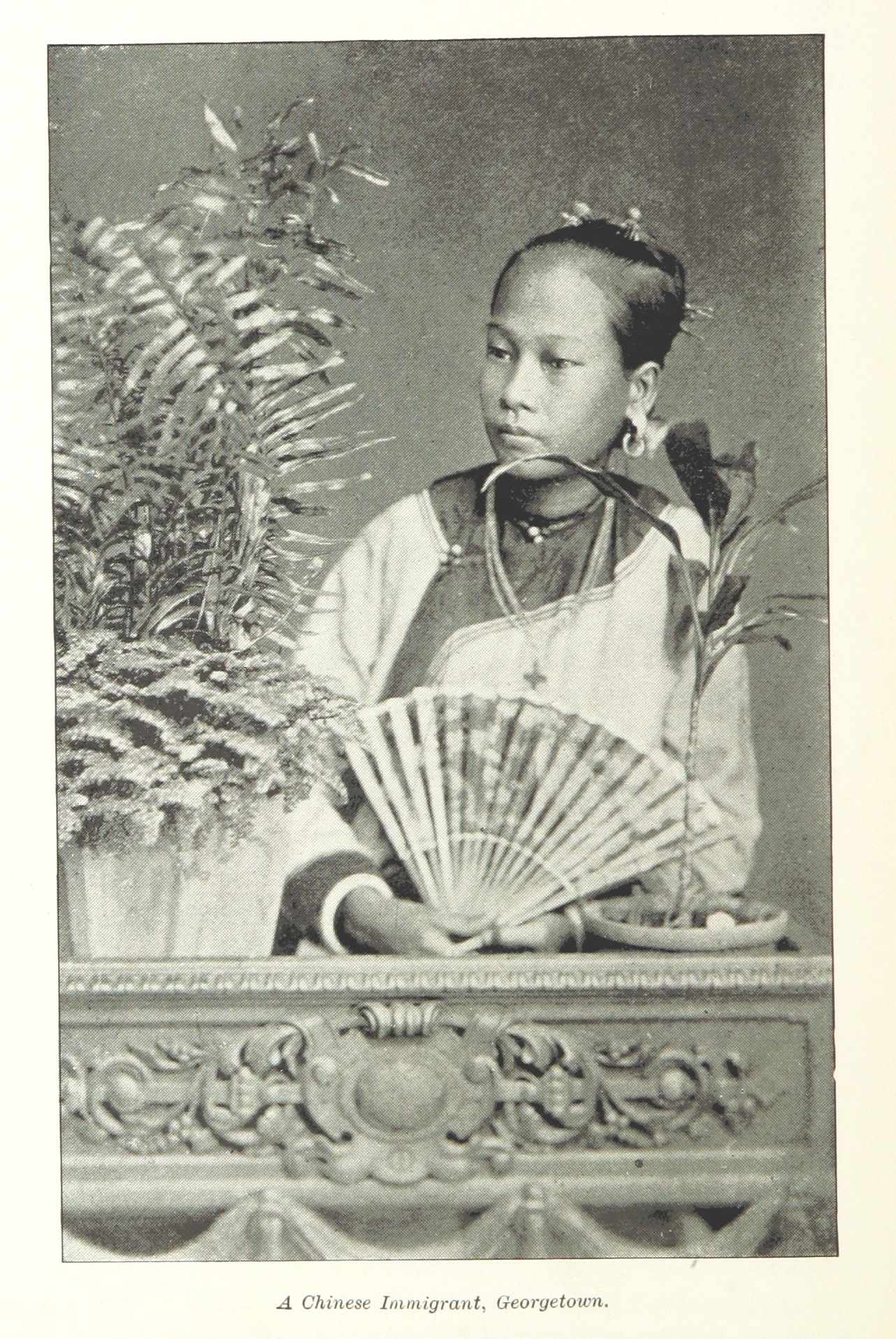

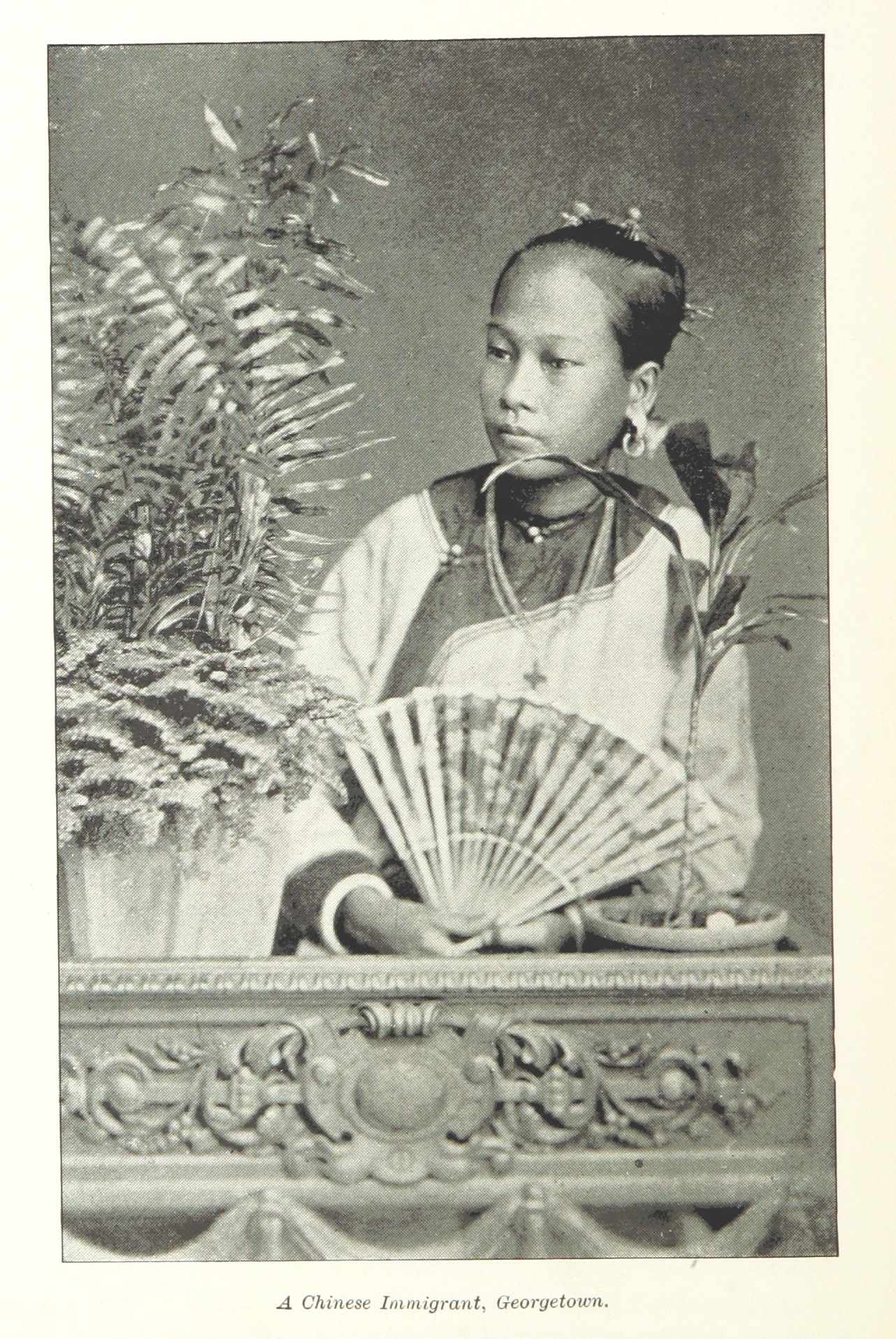

And let us never forget the Chinese. Thousands of them were indentured and worked on the plantations and endured the kind of miseries that everybody endured. And we forget about them. Bring them in. Africa, India, and China. Go for the whole body. Go for unity. Be practical.

By involving all of us it makes us stronger.

Traditional historical binaries have positioned the Caribbean within uniquely black and white framings; how has this affected or compromised the Caribbean’s cultural diversity?

Fusion and mixture and cross-cultural interactions have been part of the Caribbean from day one. From the time the Africans arrived and met the Amerindians, there was some kind of fusion going on.

It is not black and white. There are Indigenous people, the Chinese, the Portuguese, the Indians, and other ethnicities all producing. There is fusion in our music between Indian folk music and Calypso and Soca. There is fusion in our cuisine, whether it’s the Indigenous Pepperpot, the African use of yam and ground provisions, or chow mein, a national dish in Guyana and is Chinese, or duck curry which is Indian.

Sometimes we do see it as black and white, but it is not. We are a hybrid people. And I’m pleased to say that about 18% of Guyanese are of mixed heritage. That’s a good start.

How important for you are arts and culture and the work that you do to try and explain these, on one level, very complex situations?

If there is something called Guyanese-ness, then one has to go beyond, or maybe below, economics and politics into an appreciation of the arts that we create because the arts that we create contain our emotions – our soul. It’s what we empathise with. An understanding and an appreciation of the arts and of culture is important. Who said, “Man does not live by bread alone?”

How have you used literature (novels and poetry) to portray these heavy themes? Has it allowed a certain freedom of expression? Accessibility to readers?

What I wanted to do as a writer, when talking about chattel slavery and indentureship, was to drop the academic language as it were and take the subject out of books. I wanted to use a different kind of literary language, to give some flesh and pulse and heart and heartbeat and individuality to actual people, not just statistics.

As Toni Morrison said, you can write about trauma and suffering, but write about it beautifully. Use beautiful language because writing beautifully is a way of respecting your subjects. My main challenge as a writer is to write in a way that is compelling both in terms of story and in language I use.

What are you currently working on?

Just today, I signed my contract with my publishers for the appearance of my new novel, set in China and in British Guiana focusing on a Chinese Li Ji, which will come out next year.

This novel looks at Guyana just before the First World War. It’s looking at Guyana through Chinese eyes. I take some Chinese immigrants to Guyana who are fleeing their enemies from the First World War. Some of them go to Guyana, they see Indian workers, they look at the black people and they comment as outsiders.

In a sense, it’s an attempt for us to see ourselves through other people’s eyes.

In light of our conversation today, what are your hopes for the future regarding Indian-Caribbean representation and reparatory justice overall?

To my mind, the most important part of reparations is acknowledging through scholarship and education the role of the empire in all our lives: Indian, African, Chinese, Irish and so on.

It’s the acknowledgement and the writing of history books. How many books have been written about indentureship? The Ameena Gafoor Institute has the most comprehensive bibliography on indentureship anywhere in the world. And believe me, it’s a handful of books and a lot of articles. We’re at the beginning of the journey of scholarship, and to me, that education is really important.

I would love the young people in Guyana to know what chattel slavery was and what indentureship was. I see movement among the young people in Britain but I can’t say the same for the for the older generation, some of whom still have a hankering for empire or have the sense that the empire was beneficial and benevolent. London is much more diverse now. I am happy I can see things changing slowly in schools and universities from when I came in 1969. I’m optimistic that this is unstoppable and also because of people like you and your movement, The Repair Campaign, and other organisations.

Secondly, we need films for children that use cartoons and child-friendly ways of communication so that the children of Guyana can get to know about their past. You’ve got to somehow find a way of presenting this past in a compelling and attractive manner. That’s a real challenge. How do you how do you communicate a Holocaust to children without getting them completely traumatised themselves? But it has to be done.

I’m optimistic that things are moving in terms of the education system and the acknowledgement of our history. But my worry about reparations is that any money given will go to the elite. I’m part of the elite. I work and live in universities. I benefit from the knowledge of history. I teach the history. I am a beneficiary of reparations in that sense. How will the ordinary people on the bottom of the social and economic ladder benefit? There are many people in Guyana who are malnourished. Will any money go to them?

I believe in reparations but most of it must go to the people – the ordinary, common person.

I have to say hand and heart that the work that the work that you’re doing in The Repair Campaign is really as thorough as one could hope for. And the best thing about what you’ve done from what I can understand and from what I’ve read is exactly that the plans you will propose for different countries, which are practical plans. They’re about education, but they’re also about looking into women’s violence and other issues. There are those in Guyana who don’t believe they will receive a penny. And I know this is what The Repair Campaign wants to avoid by implementing these practical Socioeconomic Reparatory Justice Plans in Guyana and other CARICOM countries.

Do you have any closing remarks?

When all that is finished and when it’s time for me to die, I do not want to die as an Indian, or as a descendant of an indentured labourer. I don’t want to die as a person of colour. Or even as a man. I want to die existentially as a human being who had this thing called life for a little while. I don’t want to die ethnically, if you see what I mean.

Given the great crisis that we face in humanity, which is climate change, brown people and yellow people and black people and white people must become green people now. We’ve got to move from our present colour. We must all become green. Is that a fantastic transformation?

We acknowledge as well as move beyond our ethnicity and we suddenly realise that we have an existential threat, which is the climate.