Three Lesser Known Stories of Caribbean Resistance

March 22, 2025

By: Nyala Thompson-Grunwald and Ashley Onfroy

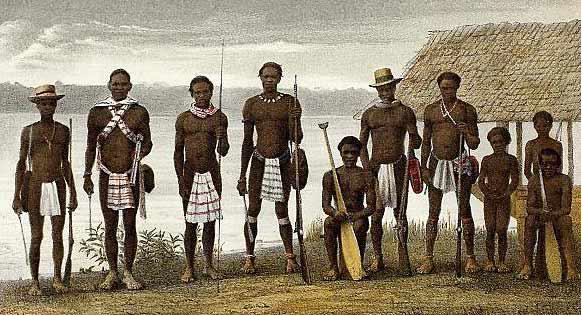

Depiction of Maroon Warriors, Suriname [image source]

As The Repair Campaign marks March 25, The UN International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Chattel Slavery, we believe it is equally important to honour these ancestral freedom fighters by remembering the numerous and continual waves of resistance led by indigenous people and enslaved Africans since the very beginning of European colonisation in the Caribbean.

In this article, we spotlight three lesser known but equally powerful stories of Caribbean resistance to colonialism which contributed to the eventual abolition of chattel slavery.

Marcus of the Woods, St. Kitts and Nevis - 1830s

Marcus of the Woods was a pivotal figure in the resistance movement against British colonial rule in St. Kitts during the 19th century. While less is known about Marcus compared to other leaders in Caribbean rebellions, he earned the title “of the Woods” because of his expertise in using the island’s dense forests to his advantage, evading British capture and launching surprise attacks on the plantations. He played a critical role in the region’s legacy of resistance.

Resistance to enslavement was common throughout the Caribbean, and enslaved Africans on St. Kitts were no exception. Marcus of the Woods emerged as a leader of a major resistance movement in the 1830s, where he led a group of runaway enslaved Africans who established maroon communities in the dense forests and mountainous regions of the island. These maroons, sometimes called “bush Negroes,” were enslaved Africans who escaped from the plantations and formed self-sustaining, hidden societies in the island’s interior.

The maroons of St. Kitts, under Marcus’ leadership, resisted British efforts to capture and re-enslave them. Marcus’s group, operating out of the island’s remote and rugged interior, engaged in guerrilla warfare against British forces. They conducted sporadic attacks on plantation estates, freed other enslaved Africans, and disrupted the colonial economy. They, never being caught, despite being termed ‘nuisances’ to public order by colonial authorities. A letter dated in 1834 states that: “no order may be expected in the country unless he [Marcus] is taken”. At the time, reports indicated that just under 100 enslaved persons were missing from plantation estates – it is presumed that they joined whatever maroon community Marcus may have been able to build.

The growing threat of Marcus and his maroons challenged the plantation system and inspired further acts of rebellion among the enslaved population. In response, the British organised military expeditions to track down and eliminate the maroons. Despite the British forces’ superior numbers and weaponry, Marcus and his followers proved elusive. The terrain of St. Kitts made it difficult for the British to locate the maroons, and Marcus’s knowledge of the island’s forests allowed him to outmanoeuvre the colonial forces for a time. Eventually, however, the maroon resistance was weakened by relentless British attacks, and Marcus’s movement was suppressed.

Though the specifics of Marcus’s fate remain unclear, his leadership in resisting British authority left a lasting legacy in the history of St. Kitts. Marcus is remembered in St. Kitts as a heroic figure who fought for the liberation and dignity of his people, playing a critical role in St. Kitts history of resistance against colonialism.

Further Reading: ‘Our People: Marcus of the Woods’, Historic St. Kitts: National Archives of St. Kitts. Available at: https://www.historicstkitts.kn/people?start=30

Boni, Suriname – 1789, 1793

Boni was a tactical Maroon chief who led two Maroon wars in Suriname in 1789 and 1793. His leadership and military strategies made him one of the most significant figures in the resistance against chattel enslavement in Suriname. He was born in the early 18th century, and emerged as one of the most important Maroon leaders in Suriname. Boni belonged to the Aluku or Bonis, a subgroup of the larger Maroon community, which included the Saramaka and Ndyuka. He led his followers to settle in the eastern part of Suriname, along the Cottica River, where they established villages and created a self-sustaining society, relying on farming, hunting, and raiding plantations for supplies.

Under Boni’s leadership, the Maroons launched frequent raids on Dutch plantations, freeing other enslaved Africans and disrupting the colonial economy. These attacks not only undermined the plantation system but also struck fear into the hearts of the Dutch colonists. Boni’s guerrilla tactics were highly effective—his knowledge of the dense forests allowed him to evade capture and carry out surprise attacks on plantation settlements and military outposts.

By the 1760s, the Dutch authorities viewed Boni and his followers as a significant threat. Boni led the Cassipera, Tesisi, and Kormantin Kodjo Maroons (450 fighters in total) to raid several plantations and start a guerrilla war against the Dutch military in 1789. The colonial government launched a series of military campaigns, known as the Boni Wars, to crush this resistance. However, the Maroons’ mastery of the terrain and their hit-and-run tactics frustrated the colonial forces.

Later, Boni’s troupes eventually moved across the Marowijne River into French Guiana, where they established a new base of operations and continued to harass Dutch plantations. The established bases in French Guiana, Aroku, and some neighbouring villages along the Marowijne River were seized by the Dutch colonial troops and Black Rangers in the Second Boni-Maroon War in 1793. The Boni Maroons retreated further south along the French side of the river. Their alliance with the Ndjuka fell apart leading to outright war between the two groups. The Boni Maroons started peace negotiations with the Dutch but the talks were delayed and considerations discarded because the Maroons considered the Dutch demands excessive. In 1793 the Second Boni-Maroon War came to an end when Boni, and many others, were killed in French Guiana by the Ndjuka.

Boni’s leadership and the resilience of the Maroons made him a symbol of defiance and freedom in Surinamese history. Although he was eventually killed in battle in 1793, his resistance had a profound impact. His efforts contributed to the eventual signing of peace treaties between the Dutch and several Maroon groups, recognizing the autonomy of Maroon communities in exchange for ending their raids on plantations.

Further reading: van Stipriaan, A. (1991). [Review of The Boni Maroon Wars in Suriname, by W. Hoogbergen]. Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe / European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 51, 145–147.

Julien Fedon’s Rebellion, Grenada – 1795

Fedon’s rebellion is an important act of resistance in the Caribbean and considered to be a contributing factor to the wider and broader attempts at freedom and the abolition of slavery as well as social and political revolution. It is called Fedon’s rebellion or revolt because it was spearheaded by Julien Fedon, now known as the main leader and central figure of the rebellion though he was assisted by a few others like Charles Nogues, Joachin Philip, Jean Pierre La Valette, Stanislaus Besson, and Jean Fedon (his brother). Julien Fédon was born in Martinique and was of mixed race heritage and a leading member of Grenada’s French community who inherited his father’s 360-acre estate, Belvedere. He was the leading figure in what became Fedon’s Rebellion from March 2, 1795 – June 19, 1796 in Grenada.

Planning for the rebellion began in March 1793, when Fédon and his enslaved began converting his Belvidere plantation into a fortified headquarters and planting crops for his army. In early June 1795, two of his colleagues travelled to Guadeloupe, then under the control of French revolutionary commissioners to receive weapons, training, and commissions (military appointments), one of which made Fédon General-in-chief of the Grenadian rebel army. On March 2nd, 1795, this force simultaneously attacked Gouyave and Grenville major towns; the attack on Gouyave was relatively peaceful, but in Grenville the white population was slaughtered. Many hostages were taken. The British had several unsuccessful attempts at conquering Belvidere, but the estate was near the top of a very steep mountain, and almost inaccessible. After the failure of one of the British attacks, Julien Fédon ordered the deaths of around 40 white hostages. Throughout the rebellion the rebel army had a system of looting, pillaging, and burning the island’s plantations, while having wars here and there with the British. Both sides attempted to capture and recapture headlands and outposts with varying degrees of success. The British Royal Navy managed to maintain an effective blockade of the island overtime, Fédon’s army became isolated and suffered from little reinforcements and military supplies. His force also paid the price for destroying so many crops the year before, because very soon there was a food shortage while the British, on the other hand, received major support. So, in June 1796, they launched another attack on Belvidere and this time it was successful. Fédon’s army was defeated, and the rebellion ended.

The island’s economy was devastated; whereas it had been an economic powerhouse before the rebellion, plantations and distilleries had been destroyed, causing around £2,500,000 of damage. It would take several years and a loan of over £100,000 from the Colonial Office for this colony to begin to recover from the damage wrought by the conflict. Fédon’s Rebellion stimulated anti-slavery debate in Britain and was used as an example in the anti-slavery campaigns that led to the ending of the slave trade in 1807.

Further Reading: Cox, E. L. (1982). Fedon’s Rebellion 1795-96: Causes and Consequences. The Journal of Negro History, 67(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2717757