The Transatlantic Trafficking of Enslaved Africans

Between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million enslaved people were shipped from Africa, with 10.7 million arriving in the Americas making the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans the “largest long-distance coerced movement of people in history.”

The transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans was driven by demand for labour as consumption of plantation produce – including sugar, rice, indigo, coffee, tobacco, alcohol and some precious metals – grew in Europe. With indigenous populations dying due to colonisation and genocide, and Europeans unwilling to make the journey themselves, labour was mainly comprised of enslaved people from Africa. Roughly one woman was taken across the Atlantic for every two men. The captains of slave ships were usually instructed to buy as high a proportion of men as they could, because a higher financial value was placed on enslaved men.

The period between 1776-1800 saw the highest number of enslaved people taken from the African continent as a whole. Records from Slave Voyages show that most of the people who were forced onto ships and taken to the Caribbean between 1626 and 1825 were originally from West Africa. Two systems of wind and ocean currents in the North and South Atlantic determined two major slave trade routes which meant Africans carried to North America, including the Caribbean, left from mainly West Africa, with the Bights of Biafra and Benin and the Gold Coast predominating.

The ports on which people were forced onto ships are named as they were then, but where possible we have defined the geographic location today:

The Middle Passage

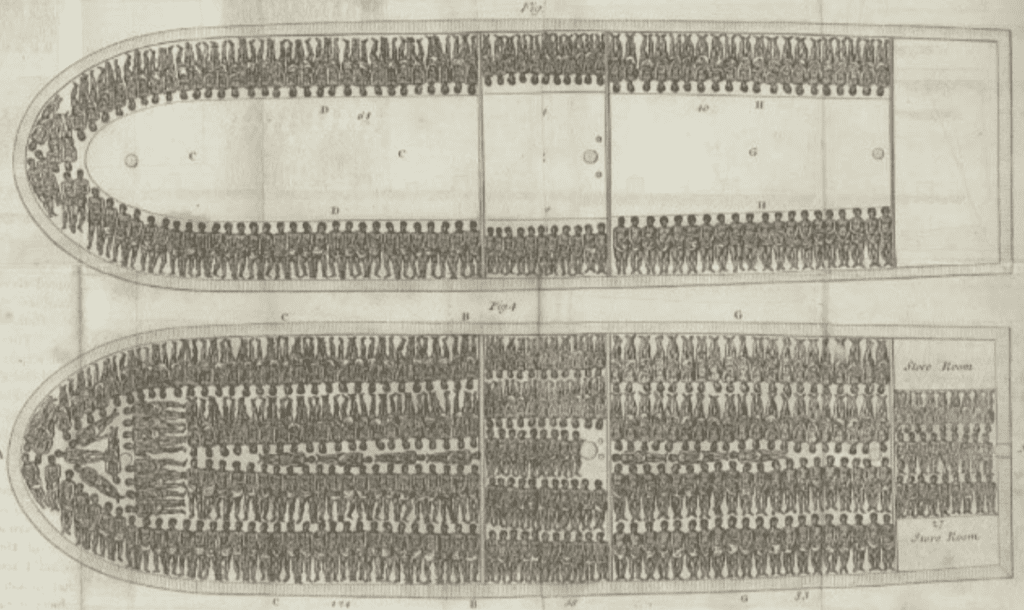

The journey that forced millions of people in slave ships across the Atlantic became known as The Middle Passage. The voyage lasted two months on average and, even though improvements in technology eventually reduced the time, the conditions were no less brutal. Ships were overcrowded and filthy with a severe lack of sanitation, leading to outbreaks of disease and sickness. Nutrition was inadequate, the heat was oppressive, and the air was rancid.

Men were packed in on top of each other meaning many had to crouch and they were often chained for long periods at a time.

Women and children were kept separate and were subjected to violence and sexual abuse from the crew. Rebellion was not uncommon in these conditions.

Estimates differ, but it is thought around 20 percent of those people on the ships died on the voyage, although the figure is likely significantly higher. It is worth noting that no European – in their capacity as convict, indentured servant, or free migrant – ever had to experience this environment, only enslaved African people.

Plantations

Plantations refer to settler colonies including farms, estates and areas of land intended (usually) for agricultural cultivation of produce like sugar and cotton. Plantations relied on the forced labour of enslaved people and death rates were high due to overwork, poor nutrition, brutality and disease. There were also many rebellions and instances of resistance on plantations.

The “Plantation Economy” caused significant underdevelopment in the Caribbean due to exploitation, resource extraction and dependency generation. Colonies were developed as export oriented and with monocrop plantations. In this economy, plantations served to facilitate accumulation and expansion of the colonisers’ markets which not only created a deep dependency, but also severely restricted the development of a domestic market or any internal dynamic in the colonial economy.

Abolition

The slave trade was abolished in 1807, but it wasn’t until 1833 that the UK Parliament abolished slavery in the British Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape and it came into effect 1 August 1834. Following negotiations between the British state and those defending the interests of the slave-owners, a settlement was reached agreeing compensation for the loss of enslaved workers. The terms of this compensation included a system of so-called “apprenticeship” which required the newly emancipated men and women to enter into another form of unpaid labour for another six years.

The Act also included the grant of £20 million in compensation, to be paid by the British taxpayers to slave owners for loss of “property.” This represents about 40 per cent of the government’s total expenditure at the time and 5 per cent of British Gross Domestic Product. Such a massive figure required the Government to borrow money to fund the Slavery Abolition Act, which was not fully repaid until 2015.

Legacy

The persistent harm and suffering experienced today by descendants of enslaved people and the region’s socioeconomic vulnerabilities are a direct result of slavery and colonisation. The legacy of extraction and dependency meant former colonies grappled with significant challenges.

To tackle uncertain labour supply, rising labour costs and the availability of land, some countries turned to indentured workers to work on existing plantations in an attempt to revitalise export industries that had dominated their economies under colonialism.

Newly independent countries were also forced to borrow heavily which hindered development trajectories of the Caribbean meaning poverty and inequity has been inescapable. As a result, the wider problem of social neglect is a common theme throughout the region with communities struggling with deteriorating socioeconomic conditions such as violence, unemployment, education and heightened vulnerabilities to climate change.

Genocide, slavery and colonialism inflicted deep and lasting damage while providing economic benefit to the colonisers. Some of the institutions supported by benefits made possible through enslaved labour still occupy prominent positions in modern-day Britain. Recipients of compensation included some of the wealthiest and most powerful people who were involved at a high level in politics, religious institutions, financial institutions and cultural institutions. Moreover, the wealth generated from the labour of enslaved people was invested in a variety of manufacturing and commercial enterprises in Britain. The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery estimate that between 10-20 per cent of Britain’s wealth can be identified as having had significant links to slavery.

Sources and Further Reading

Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery

Naomi Fowler: Britain’s Slave Owner Compensation Loan, reparations and tax havenry.