The Unique Brutality of Chattel Slavery

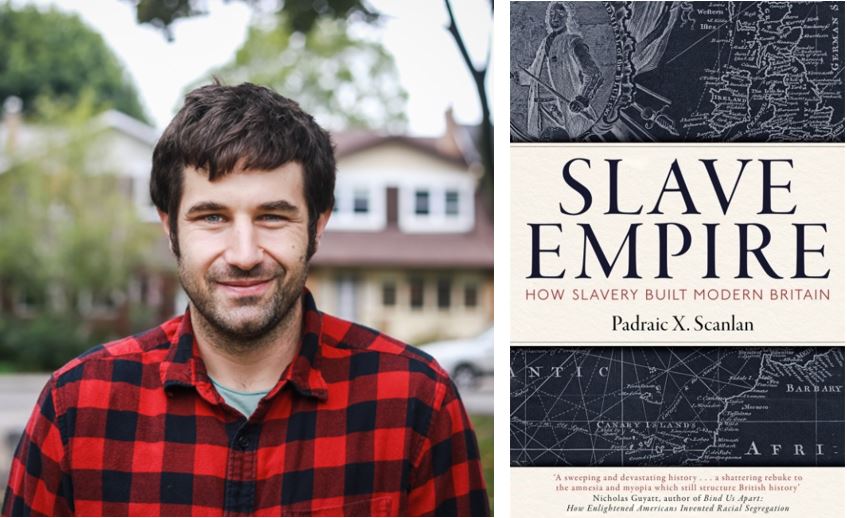

The Repair Campaign interviewed Dr. Padraic Scanlan from the University of Toronto about reparatory justice and his book Slave Empire: How Slavery Made Modern Britain (2022).

February 27, 2025

Dr Padraic X. Scanlan is Associate Professor at the Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources, at the University of Toronto.

Could you introduce yourself and your work?

Sure, my name is Padraic Scanlan. I’m an associate professor at the University of Toronto, where I teach history in two departments, the Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources and the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. Since my PhD research through to fairly recently, I’ve worked on the histories of British slavery especially in the Caribbean and also British antislavery and emancipation.

I’m the author of two books on that subject. The first one is called Freedom’s Debtors. It was published by Yale University Press in 2017. And it’s about the way that the abolition of the transatlantic, or at least of Britain’s share of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, became a way of initiating a new program of colonial rule in West Africa.

And then I followed up on that relatively narrow and quite academic book intended mostly for a specialist audience with a book for general readers published in 2020 called Slave Empire: How Slavery Made Modern Britain, which expands on some of the arguments that I made in that more focused book and tries to explain the way that the rise of mass enslavement in the Caribbean, the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, and the rise of British industrial capitalism were connected to one another. And to show how crucially the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean in 1833 coming into force in 1834 wasn’t actually the beginning of a process of liberation as much as it was a way of reconstituting imperial power in a new, and I would say arguably even more forceful guise. It was a transformation from a form of imperial power based on the blunt instrument of coercion and violence into a new form of imperial power that maintained much of that coercion and violence, but was able to cover itself in what British imperial officials would have called civilization. The idea that rather than an empire based purely on extraction, all of a sudden Britain’s empire was now based on advancing and promulgating and nurturing a set of British values around the world. And so those themes have been the major arguments that I’ve tried to make in my work on slavery and antislavery.

Thank you. In your book Slave Empire, you go in a lot of depth about the systems of chattel slavery under British imperialism. How can reparations advocates better communicate the fact that chattel slavery was unique from other forms of slavery?

There are three ways of really narrowing in on that answer that really differentiated the transatlantic slave trade from the many other forms that enslavement has taken in human history. And that’s not an incorrect claim – slavery was not invented in the 17th century by European empires in order to grow plantation crops, but there are substantial differences.

1. Chattel slavery was racialised

The first is that slavery in the transatlantic slave trade was explicitly racialized. That is probably the most prominent and most important feature or defining characteristic of the transatlantic slave trade. You know, in the era of the Roman Empire, when millions of people in the Roman Empire were enslaved, there wasn’t one place that enslaved people came from. There wasn’t one geographic origin for enslaved workers in the Roman Empire. One of the things that the transatlantic slave trade did was to associate enslavement with African heritage. So that was one of the first things that really differentiated the transatlantic slave trade from other forms of even really substantial mass enslavement in human history. It was the first time that that had become a justification for enslavement. I think one of the interesting things that I’ve tried to bring out in my work is that originally the transatlantic slave trade wasn’t initially explicitly racialized, but it very quickly became explicitly racialized.

European empires establishing colonies in the Americas needed labour. And enslaved Africans became a convenient source of labourers who were far from their homes, didn’t speak the language, were often from multiple different places, often didn’t have a language in common. So initially, the transatlantic slave trade began as a money-making expedient, a way to exploit people in order to make as much money as possible as quickly as possible. But then over time, as plantation slavery, particularly growing sugar, but also later cotton and other cash crops, unfolded and expanded, race became not a secondary adjunct to the process of enslavement, but a major justification for it.

So it went from being ‘Africans who have crossed the Atlantic are easily exploited’ in the Americas to being, ‘people of African descent are made to be enslaved’. And so that was one of the significant differences. And I think that that’s something that differentiates and really has been one of the most noxious consequences of the transatlantic slave trade.

In the Roman Empire, the Scythians were often enslaved and exploited. The Gauls were often enslaved and exploited. But there isn’t a legacy of anti-Scythian or anti-Galic racism in the present day. Those distinctions have disappeared in a way that the distinctions created by the Transatlantic slave trade have not disappeared. So that’s one reason.

2. Chattel slavery treated enslaved Africans as a unit of capital

The second reason has to do with capital. So Roman slavery was pre-capitalism. Slavery in the Indian Ocean was maybe proto-capitalist, but certainly pre-capitalist. Slavery in West Africa was complex and pre-capitalist. These were all versions of enslavement.

I think one of the things that people make apologies for Britain’s involvement in slavery, try to lean on is this idea that to condemn transatlantic slavery is to somehow not to condemn other forms of enslavement. I don’t think there’s anything that’s mutually exclusive about saying that the transatlantic slave trade was a trans-historical evil and saying the same thing about Roman slavery. And I think that that’s a kind of sleight of hand that appears in apologetics sometimes.

But one of the things that distinguished the transatlantic slave trade was the idea that every enslaved person became not just legally property, which was a feature of enslavement before, but also legally property that could always be exchanged at any time for money. And so some historians call that the chattel principle. The distinction that an enslaved person wasn’t first and foremost even a unit of labour as much as a unit of capital. And that’s a really big difference. And that principle unfolded in the many codes that Britain’s Caribbean colonies enacted that governed the ways enslaved people could move.

It meant that even a person of African descent who was free was always vulnerable to re-enslavement. Both because they could be seized as capital, but also because the racialized nature of transatlantic slavery made them vulnerable. So those two intertwined features of transatlantic slavery really differentiated from previous forms of slavery.

3. The modern world was built on Transatlantic chattel slavery

And there’s a final one, which is that transatlantic slavery happens to have been the system of mass labour that developed both Britain’s imperial capacity, especially in the 18th century, and also later developed much of the United States’s industrial and commercial capacity in the 19th century.

So transatlantic slavery is also different from earlier forms of mass enslavement because we live in a world that very concretely was made by transatlantic slavery. That doesn’t mean that every feature of the modern world is shaped by this system, but it does mean that we live in a very proximate and very intimate way in the world shaped by transatlantic slavery.

What resources can you recommend for understanding the economic relationship between chattel slavery and the Industrial Revolution, particularly in terms of the capital that was generated from slavery and used to fuel the industrial growth?

There are a few books and one historian that I think are worth looking into.

The historian Chris Manjapra, who works I think at Tufts University in the United States, has written some pretty good essays and a short book titled The Black Ghost of Empire (2022). His work offers a solid overview of how the capital from chattel slavery was laundered to become the capital post slavery. The historian Peter James Hudson has a good book on later Caribbean history, the economic historian Nicholas Draper has a book called The Price of Emancipation, which is probably the best, most detailed kind of technical analysis of the financing of emancipation.

Manjapra’s work helps to provide the framework while Draper’s book is much more focused and much more narrow. It’s much more like a monograph really for specialist historians, but it has real concrete data. And so I think together you have a framework and data that might be helpful.

In your books you mentioned that abolition wasn’t really about ending slavery, but rather about finding ways to continue unfreedom in different forms, particularly in the Caribbean. Could you elaborate on how the aftermath of chattel slavery especially in the Caribbean, perpetuated unfreedom?

What I’ve tried to bring out in my work is the way that emancipation was never really conceived of as immediate emancipation. It was never conceived of as a moment of abrupt rupture between an era of enslavement and an era of freedom. Instead, it was conceived of by British officials, not by people living in the Caribbean, not by enslaved people, as the first step on a pathway from enslavement to wage labour, ideally low paid wage labour on sugar plantations. And you can see that in the way that British antislavery presented its ambitions to Parliament.

As a quick potted history, every year from 1787 on, William Wilberforce presented a motion to parliament, which is often presented as though it were a law, but it was in fact a motion to abolish the British slave trade. And so the first question that is not always asked is, ‘why was the slave trade the first target rather than slavery itself?’ And the answer is that many of the abolitionists, at least in the kind of elite circles that Wilberforce moved in, conceived of the end of slavery as something that could not happen abruptly. It had to happen slowly and it had to preserve the existing social order.

Wilberforce’s motion was premised on the idea that if Britain stopped trafficking a fresh supply of enslaved people across the Atlantic:

- Enslavers in the Caribbean would be forced to improve living conditions for enslaved labourers

- They would be forced to accept the work of Christian missionaries among enslaved labourers

- They would be forced to accept greater legal restrictions on how they could treat enslaved labourers

- and slowly over time, slavery would disappear.

And so in 1807, the Slave Trade Act was premised on that idea that without the supply of enslaved labourers flowing into the plantations, slavery would wither over a period of five ten, fifteen, who knows how many years. And for Wilberforce, who was deeply, deeply religious, he conceived of that as an acceptable, because in his view, although he probably loathed the violence of slavery, I think what really animated Wilberforce was the idea that enslaved people didn’t have the ability under slavery to hear the gospel. So they couldn’t be offered the same kind of ecstatic conversion that Wilberforce thought every human being was entitled to. And that’s what he found really morally appalling about slavery in addition to its violence. And so, that’s a very different impetus for abolishing slavery than we might think of.

He certainly thought enslavement was wrong, there’s no question about that. But he also thought that it was better to preserve slavery and slowly reduce it over time than it was to kind of abolish it immediately.

That assumption obviously didn’t work out. Slavery continued to thrive as an economic system after the abolition of the British slave trade for a whole range of reasons. But it was really the series of rebellions led by enslaved people in 1816 and 1823 and then in 1830, 1831 that kind of made it clear that without the abolition of plantation slavery, there would be no peace in Britain’s colonies. It was just impossible. Rebellions seemed to be becoming more frequent, more violent, more destructive.

So British legislators looked for a path through what they called the amelioration of slavery, which was an official government policy to figure out how to slowly erode this system. And so the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act ended the status of ‘enslaved’ for hundreds of thousands of people, but replaced it with apprenticeship.

Apprenticeship was an ideologically interesting period in that it says so much about how Britain thought about enslaved people, how Britain thought about all labourers who were not British wage labourers living in Britain. It was this era when people who had once been enslaved would now be expected to work for 40 and a half hours a week for the people who had once claimed to own them. And then the rest of the time was quite literally their free time, which they were expected to sell to employers and to learn how to become wage labourers.

And apprenticeship collapsed earlier than it was supposed to because it was completely impossible to maintain. It fell apart in 1838. But it still was premised on the idea that enslaved people should continue to work for plantations. It was to teach people who had every reason to despise working on sugar plantations that in fact, the problem with plantation labour wasn’t the plantation labour itself, it was enslavement.

And so if you could persuade or force or compel or cajole formerly enslaved people to be wage labourers on plantations, then Britain could have its cake and eat it too. It could be the empire that abolished slavery in its plantation colonies while also being an empire that continued to have plantation colonies.

That’s a story of emancipation that’s a lot less satisfying than perhaps the kind of heroic narrative that you might hear about it. It’s a lot more abridged and a lot more kind of circumscribed by what Britain wanted.

In your book Slave Empire, there is a quote: “the Caribbean was a creeping frontier of money, human suffering, dispossession and ecological mayhem.” While this lived experience is known in the Caribbean, there seems to be an amnesia or erasure of the depth of that colonial history in the UK. How can reparations activists confront this erasure and communicate the ongoing impact of these traumas?

I think there are two answers that come to mind right away. First, it’s about making the case to people living in the UK. One of the biggest challenges in advocating for reparations, particularly the practical case rather than the moral one, is the current economic reality in Britain. Standards of living are collapsing, incomes are declining, and Britain’s national prestige is in freefall. It’s not the country it once was. Convincing someone in, say, the deindustrialized potteries that their government should allocate significant funds for reparations for mass enslavement is a tough argument to make when they’re struggling to make ends meet.

One way to approach this might be to highlight the connections between the systems of exploitation created during slavery and those affecting vulnerable wage workers today. For instance, plantations were, in a sense, among the first factories of the British Empire. While Arkwright’s factories in northern England had around 250 workers, plantations in Jamaica or Barbados often had 500 to 700 enslaved workers. The organizational methods, task orientation, and the disposability of labour we see today were, if not directly invented on plantations, certainly refined in conversation with them.

W.E.B. Du Bois argued there’s a bright line between enslaved and free labour, even the most debased and degrading form of free labour, but it’s still a continuum. The systems that are making you miserable in post-industrial Britain are the systems that slavery made. If you’re being ground down as disposable labour for capital today, remember there were people 250 years ago literally ground down as disposable labour for capital. There is space for recognizing that the way we think of labour in all of its forms in the present is influenced by transatlantic slavery. And you can see the seeds of that in emancipation, the transition from enslaved labour to cheap wage labour. The bright line of slavery is erased.

It’s not to say that there’s no difference between freedom and slavery, but I think it is worth noting that many of the features of freedom that we all live with, especially in our working lives, and the features of the kind of dominance of capital over labour, those are features that are made in the era of slavery.

This isn’t to say that emancipation wasn’t a monumental achievement—it was, both legislatively in Britain and morally for formerly enslaved people in the Caribbean. But it’s worth acknowledging that many aspects of the “freedom” we live with today, especially in our working lives, were shaped by the era of slavery.

So, a possible argument to make to people in the UK is this: reparations isn’t a gift to the Caribbean. It’s reparations for the whole system. It’s just the Caribbean bore the brunt of it, but the average British taxpayer is also bearing the brunt of it in a different way. Reparative justice isn’t about taking from you to give to somebody else. It’s to give to somebody else so that everyone can benefit from the further outcome.

In the Caribbean, the argument is easier to make. The ecological damage alone is undeniable. For example, Barbados suffers devastating hurricane damage partly because its forests were cleared for plantations. The ecological consequences of the plantation conquest are so transparent in many parts of the Caribbean. And they’re vulnerable to climate change, which is a consequence of the acceleration of the exploitation of fossil fuels from industrialization, which is not a one-to-one direct consequence of plantations in the Caribbean, but was certainly a very powerful source of momentum for industrialization.

I think that the real struggle is making the argument to people who feel like their lives are getting worse in the present. And I think that there is a way of connecting this history of exploitation to present-day exploitation that makes that argument more concrete.