Memory and the Arts

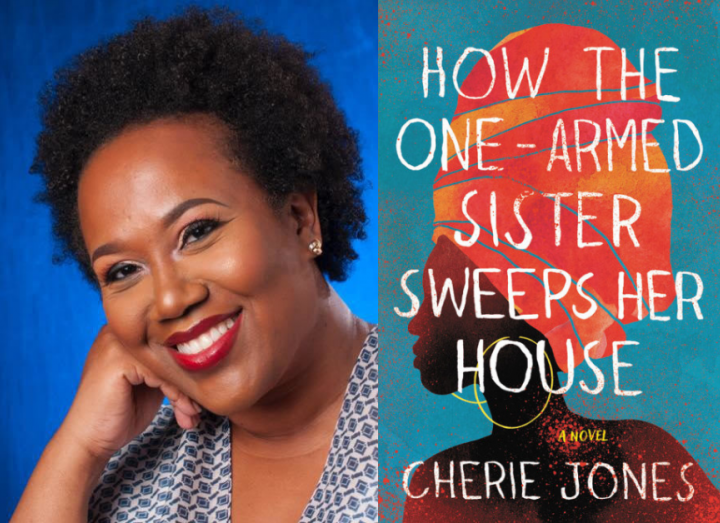

The Repair Campaign spoke with author and attorney Cherie Jones about her creative writing process, and its role in healing past trauma by remembering stories that are often left out of history.

March 28, 2024

Tell us a bit about yourself, your background and the work that you are interested in.

I am a creative person, first and foremost. I usually express myself in my creative writing, but I also am an amateur photographer, amateur furniture restorer, and textile designer. Quite apart from that, I am a lawyer by training and have been a lawyer now for about 27 years. I’m a mom of four beautiful children ranging in age from eight to 27 and I live and work in Barbados currently.

In terms of my interests, I am very much interested in how literary and cultural expression contributes to social change. My academic research so far has centred on how the ways in which we write about domestic violence or gender-based violence contributes to attitudes about it and therefore how that might be harnessed to contribute to changes that we would like to see as a collective group – nationally, regionally and internationally.

Can you describe your latest book, ‘How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House’ and how you find inspiration as a writer?

The book is about a very young woman in Barbados in the mid-1980s, who lives on the beach with her husband. The 1980s was a period of time when I personally was growing and starting to understand the world around me more. When we meet the main character, she’s about to give birth to her first child on the same night that a wealthy, white tourist is murdered further along the beach on which she lives. The novel is about how the birth of that baby and the murder of that tourist are connected and explores issues of violence, class and colour at the time.

The inspiration for the novel came about while I was living and working in the UK. I was on the bus and this character popped into my head and started to tell me this story. I was riveted by the story, but what was fascinating for me was the fact that I felt particularly well-placed to serve that story. My lived experience, my skill such as it may be, and my perspective help me to access, polish and present these stories to anybody who is interested in reading them and hopefully to impact each individual reader in a way that eventually will lead to change.

For the book I’m writing now, inspiration came when I visited a cocoa estate in Trinidad in 2019. I remember I walked across a field and there was this little stone house with a red roof in the distance and I was just mesmerised by this house. And as I stared at this house in the distance, right then this character pops into my head about a very young girl in the immediate post -emancipation period. I started to hear this story and though I might not have been aware then of exactly what this story was going to address, I knew that there was something there for me to work on. Part of the work for me as the writer is going into that haze and being receptive to what wants to be expressed through that story. It’s as if the stories exist independently of me and somehow I’m able to access them, to remember, to tap into some sort of physic memory that goes back several generations.

Can you expand on what you mean by memory and psychic memory?

I think of physic memory as a sort of ingrained knowledge, passed down through the generations without communication through the five senses. It’s a remembering of things we haven’t been told. Part of what I’m exploring in the book I’m finishing now, is about trying to reclaim the truth of a past experience through the psychic memory

For example, one of the main characters in the book I’m working on is a trans woman, whose story is a reference to one of the key cultural icons we have in Barbados called Mother Sally. Mother Sally is a woman with very big breasts, a very big behind, and has become really commercialised, dancing for the tourists every time a cruise ship comes in. A lot of what I understand to be the significance of that character is lost in the commercialisation of it.

Some research suggests Mother Sally is based on an African character that celebrates fertility. But if we look closer at Mother Sally, she is traditionally a character played by a man – the bosom and behind are put on and usually Mother Sally would wear a mask to cover the man’s beard or some of the obvious male features of the person who inhabits this character in the performance or masquerade. And I thought, this is a real far cry from the Mother Sally that we see now, and I wondered why. Although I’ve done research into historical records and references, I’ve also formed my own understanding of what Mother Sally meant and why, based on that process of reaching into that memory to find that story, and that is part of what I mean by exploring psychic memory.

When I try to access these stories, the collective memory of generations allows me to access them. I know that might sound a little unusual, but I do think there’s something there. Sir Hilary Beckles talks about diseases that we have inherited with links to slavery, and other researchers reference a “genetic memory.” I think there is an element of that in what I’m exploring, and that it’s possible that, in the same way we’ve inherited diseases across generations and things that may not necessarily be to our advantage, we have also inherited knowledge above and beyond what we’ve been told about ourselves.

Then there is the question about how much of our lived experience and our culture are we willing to ‘sanitise’, or sell, or give up to meet a perceived economic need? And in what ways have we already done that? In many cases, we play along with that as there’s a national interest in making sure tourists keep coming – particularly for economic reasons. For me, Mother Sally is one of those ways. And in my work, I’m trying to go back, to reach beyond, and to present what I understand to be the reality of her significance and her experience.

What does memorialisation mean to you?

Memorialisation is a means of recognising and remembering aspects of history and working on acknowledging some of what has happened in a way that allows us to learn and grow from those past experiences. It’s being able to look at historical events and determine how we want to remember and learn from those aspects of our history, and what we can do to perhaps right any historical injustice that has persisted in our present experience.

Memorialisation isn’t a static thing either.

I’ll give you an example. There’s a site in Barbados that’s sort of a renovated and repurposed plantation. It’s a beautiful space and has a market, all these quaint shops selling things and there’s a little festival going on right now. I visited recently and I saw a little plaque on the wall, which, despite being my fourth visit, was my first time to notice it. It mentioned how dangerous working on the plantation was and referenced an incident where an enslaved person, working as a boiler, was covered in boiling sugar after a bolt came loose. His skin was peeling off as he went to the hospital and he died within an hour. I thought to myself, here am I in this beautifully renovated space with all these wonderful things to experience, but I couldn’t help but think, there is blood on the spot that I’m standing. And now the walls are pink and there is this tiny plaque talking about the horrific way in which this man died. It was just one of those moments where I got goosebumps, like I had some sort of dissociative experience.

And then there’s the other thought that some wealthy developer made this into a tourist attraction but that little plaque may be all the boilerman gets. And how much of the profit that’s generated goes into the surrounding community or the descendants of those enslaved there?

It’s a complicated discussion for some people. We do depend on tourism. It is one of the pillars of our economy, but it’s almost as if that boiler dies twice because he’s almost an afterthought in our memory and our current experience of that place.

So, I guess monuments and murals and so on certainly have their place, but it has to be more than that. I think it also should be about not only remembering, but rectifying, repairing. It’s about honouring in a constructive way and about how can we right that wrong. How we can change the way we think about ourselves and about our past in order to go forward in a way that helps us to really stand on those shoulders and lift that memory and that experience. And to me, that’s partly through writing and storytelling.

How would you like to see chattel slavery memorialised and commemorated in art or in literature?

I think it’s about reclaiming that story because a lot of times all we have is what’s been told to us and, too often, those accounts are written by white men who were part of the plantocracy at the time. So, for me, memorialisation is about remembering what has happened and giving that missing perspective.

We have a few accounts from enslaved persons about what happened, but I think there are narratives that have not made it to today. I think giving voice to those is part of the role of writers and of artists. To pull that story into our present consciousness in a way that is helpful to us and enriches our experience, our knowledge of who we are and how we go forward. We don’t always appreciate the power of that story to change us, to change the way we think about ourselves just by putting forward that other perspective. For me, that is key to my work as a writer as it relates to memorialisation because what I’m doing is I’m going back and I’m giving that alternative perspective now. I’m giving voice to that which we really might not have heard before.

What is your opinion on reparations?

I think reparations are absolutely necessary. It’s hard, especially from the legal perspective, to right a wrong that you do not first acknowledge and express regret for. But that is not the end of the story because whatever actions were involved in that wrong have long-lasting repercussions and cannot be remedied by a mere apology, however sincere it may be.

In the Caribbean, there are some social wrongs, inequalities and disadvantages that persist even now, generations after emancipation. So it can’t just be, “well slavery is over, we’re sorry about it but let’s just get on with our lives.”

For reparations and reparatory justice, it’s about how it happens. We want to make sure it happens in a way that is effective at seeking to level the playing field in whatever way we can and develop our community as a whole because healing has to happen across the board.

How do the creative arts fit into this?

There needs to be more acknowledgement of the role that creative artists play in the process of achieving repair. Creatives, visual artists, literary artists, dramatists, etc. all have a role to play and it’s not only about being able to go back into our memory and history and tell those stories. It’s also about how we signpost how we go forward. It’s one thing to say, this is where we came from and look at what happened historically but it’s another thing to say, this is where we came from, this is how it impacted us and how it continues to impact us now and here are some possibilities for how we might go forward from here.

I don’t believe that collective change really happens without individual change, and I think that’s one of the things that in my view some people get wrong. We kind of hope to change attitudes by passing laws that have collective application or just putting certain things in place without focusing as much on the individual change that’s really required in order to bring about change at the community level, national level, regional level and international level. I think that literary art, and art in general, is particularly well-placed to do that – to impact the individual, spark imagination and act as a signpost to what a new, more just, more socially equal future could look like.

I am also of the view that sometimes the change that my work will inspire in the individual is not totally in my hands. That’s why I have this concept of serving a story, because whatever you get from any piece of art or creative expression, is partially determined by what you bring to it and your lived experience, what’s your lived experience. So, it’s a joint process that we’re undertaking. The reader interacts with the narrative and they may get things from it that I might not necessarily have consciously intended.

Any final thoughts for us?

While I believe that change happens at the individual level, I think that achievement and realisation of that change requires a community effort. When I write a book, it’s not always with a defined intention to preach on a particular matter, to say this is how we should think about domestic violence or gender-based violence, for example. It is partially to say, this is my lived experience, this is what I’ve observed. Is this who we are and who we want to be? Should this be this way? And if not, what else is possible? And that is part of the work for me as the writer. It’s kind of going into that haze and figuring out what this story is and presenting that story to readers in a way that gives voice to the unspoken and hope for the future.