Barbados’ Efforts to Memorialise Chattel Slavery

The Repair Campaign spoke with Rodney Grant, Programme Advisor for The Prime Minister’s Office of Reparations and Economic Enfranchisement in Barbados about recent memorialisation efforts across the island.

March 28, 2024

Tell us about yourself and the work you do.

My name is Rodney Grant and I’m Program Advisor within the Office of Reparations and Economic Enfranchisement here in Barbados. It’s a recent establishment by the Government of Barbados and part of our work is to oversee the Reparations Task Force which is something that was mandated by all CARICOM countries to carry out some of the work at the national level. We work to bridge the gap between what’s happening on a political level and what’s happening on the grounds in the lives of everyday people.

There is a constant tension between the past and the present that a lot of our citizens have not yet overcome. People are still asking questions about why we want to look back, even as it relates to Emancipation Day. A lot of Barbadian people don’t think the issue of slavery is important to us now. That’s why we constantly push education and sensitisation work. We have to bring our people along. They have to understand why reparations, why now and why this is important to us as a people who are still struggling coming out of slavery.

Could you describe the tension that exists in how Emancipation Day is memorialised? What suggestions might you have to navigate through it?

A lot of this generation still struggle with the question of why we put so much effort into things like Emancipation. They think it’s something that happened years ago and that we must forget the past. And the older persons who were born in the 1950s and would have experienced some of that colonial linkage, they are still very much committed to that colonial enterprise. So that’s why there’s still these contestations and tensions that exist philosophically among many Barbadian people about the notion of looking back and why we should celebrate certain things.

Even with our Emancipation celebrations, we focus a lot on education. Over the last three years, the Minister has indicated that we roll out a very stringent program focused on education. We spent a lot of time in schools building out the emancipation story, even before we get to August 1st. We are probably one of the only countries that have a whole season of Emancipation events starting on April 14th with the celebration of the Bussa Rebellion and finishing on August 27th, where we celebrate Jackie Opel Day.

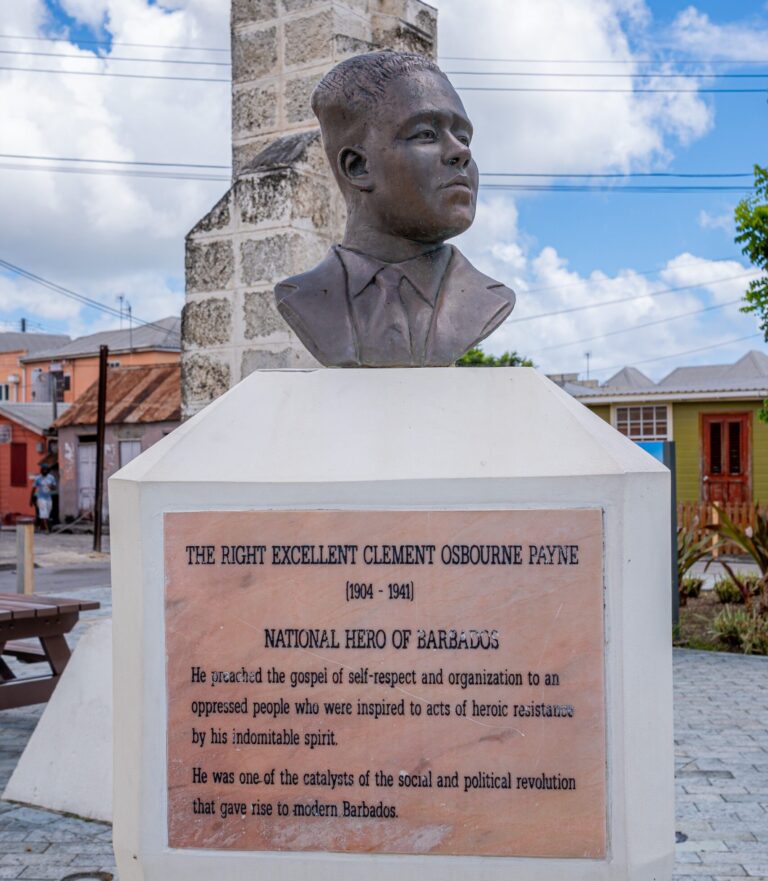

In between, there are many other days that we pay homage to. We feel that it is important to build out a story around each of these days, and to memorialise them so our young people can understand how they are connected to these events and the people that came before them. For example, if not for Bussa and the Bussa Rebellion of 1816, who knows how long chattel slavery would have gone on for? The very freedoms that our people enjoy today, our ancestors fought for. They suffered and died to ensure that you have the freedoms that you enjoy now. Look at one of our national heroes, Frank Walker, who fought for better rights around labour and trade, or Clement Payne in the 1937 riots.

We are trying to get our young people to make connections around these events and the people associated with them by rooting our emancipation celebrations in history, so they are not just seen as days of dance and fun and frolic.

How can we memorialise this history and make it relevant to young people?

Art is a very powerful way of telling stories and, with this generation, you have to find visual ways to connect. We feel that art is one of those personal ways in which we can reach people because it is subjective, it allows you to bring your own interpretation to the picture that is before you. We also felt it was important to start this process first within schools and allow students to interrogate the painting from a subjective perspective, bring their own understanding of what they see.

Using art, the Office of Reparations has found the mural concept an effective way to memorialise history. You would have seen the mural that we commissioned at the Spring Memorial School and we just did another in the north of the island in St. Peter. The mural at the Springer Memorial School paints the picture from the past to the present – it goes all the way from enslavement to modern day Barbados. It uses images of the University of the West Indies to make the connection that free university education didn’t just happen. It happened because people suffered, fought and sacrificed for you to now have free university education.

We also want young people to share their own stories through art and on social media. Let them tell their story and see how they interpret that journey from what our ancestors would have gone through to what they enjoy now in terms of freedoms. Because freedom is something that none of us should take for granted. There were times when our ancestors worked for nothing. All of their work was to build somebody else’s family, somebody else’s economy, and none of it went to them. Their labour was in vain. Now, people labour for themselves, to build their own families, to build their own economies and to build their own futures. Memorialisation through murals helps to tell the story in some of those ways and to give that subjective interpretation.

How has memorialisation become a site of contestation?

We had a lot of controversy and contestation around the Bussa statue. So much so that they changed the name from Emancipation Statue to Bussa Statue. The Emancipation Statute was established in 1985. Some advocates thought that it should commemorate this one freedom fighter, Bussa, because of the significant role he played. Through a lot of advocacy, it was then changed to Bussa Statue in 1998. It was brought to parliament as a private resolution by a then member of parliament, Don Blackman.

But in my mind, I still feel that we need something to represent Emancipation because it wasn’t just one man’s journey. It was many people’s journey. And while it’s good to single out individuals, it’s also good to represent the collective.

When it was first done there was also a lot of contestation around the fact that Bussa was naked. People felt you need to put clothes on him. And even when the artist, Brut Hagen, went back put a wrapper around him, people still complained, and felt that it should look a different way.

We will always have these different contestations because art is so subjective – murals and statues are art and people are going to have their differences because of historical inferences. But the concept of memorialisation, the concept of building out images that reflect us and our history, and the stories we want to tell our people are important, and we have to determine, as a country, what are the stories we want to tell about this journey. Because at the end of the day, you have to see things that reflect yourself.

Do you think the Barbadian government has done enough to memorialise the history and the stories you wish to see reflected?

I would say we’re getting there. We haven’t in the past, but we’re getting there.

We’ve recently built out a space with a beautiful monument that reflects the role that the Barbadian family would have played post-slavery, post-colonialism in rebuilding Barbados. It now houses all the images and the stories of all the national heroes – it is a beautiful monument of the Barbadian family that replaced where Nelson used to be. We only launched it last year, November 2023.

The city is now very much reflective of this new thrust in heritage tourism. When you go just to the south of what we now have as the monument to the Barbadian family, you will find a rebuilt Golden Square where we have the Clement Payne bust. That space is now also built out beautifully and it has all the last names of almost every Barbadian. It is a space where performances can happen, or where people can just sit and reflect.

We just also renamed our bus terminal to the Granville Williams Bus Terminal. Granville Williams would have one of these spiritual Baptist persons who brought spiritual Baptist faith back to Barbados. This is important to this whole concept of memorialisation and regaining our history because it is a spiritual practice that is very reflective of African heritage. Granville Williams spent a lot of time and energy in rebuilding aspects of African spirituality through the spiritual Baptist faith and he carried the torch championing freedom of religion.

We’re beginning to look around the country and look at where we can increase our memorialisation efforts because we believe these things are important. We have to tell the stories of people who impact our journey in a very positive way so that we can strike the balance with some of the horror and the bad things that happened.

Do you think it would be good for there to be collaboration across the Caribbean to do something that memorialises the region and the struggles in its history?

Absolutely, simple answer. Because by doing that, we get a chance to tell our story in our own way. We get to bring to life these images across the region and show the connectedness in our history, our journey and our experience. So absolutely, I think it only serves us well.

Institutions like CARICOM have to find a way to make the link with what they do and ordinary people in countries. CARICOM manages things like trade and investments and so on at the political level. But we have to find a way to make these things meaningful or make sense to ordinary people, otherwise the work becomes somewhat useless or worthless. That’s why, for me, when we think about reparations especially, it is so important to do the education among ordinary people – school children, the man on the street, the vendors, farmers – because these things are important to them and this way you build purpose. Our people need purpose and history and sites of memory can provide our people with a purpose.

So how do we get purpose? It has to be driven by something and it has to be rooted in some deep philosophical underpinning. I think one of the things that could connect us all in this region and give us a common purpose is our history, our common identity, our common journey. We all shared that common journey of slavery, emancipation, colonialism, post-colonialism, independence, and now whatever it is we are fighting for in terms of post-independence. We have that shared journey in this region and the common thread that binds us is that constant struggle to assert ourselves, to assert our identity, who we are as a people and our purpose in this global space.

Our common journey, our common identity, our common struggle is absolutely important. But what is also important in all that is how we then relate these stories to ordinary people? How do we allow ordinary people to connect with these stories and this journey?

How important is the role of memorialisation in reparations?

Memorialisation is about repair.

Financial reparations are part of the process but that is not going to resolve issues of identity, who we are, how we treat each other, how we deal with family, how we deal with some of these bad colonial things that we are still struggling with. The larger issue of reparations is our own journey in reclaiming our history that was erased by colonisers and understanding our identity as a collective. To participate in national consciousness and nation building, we have to move together as one. We move together as one nation, understanding our collective history and our collective journey so that we continue to rebuild who we are as a people and build up our educational system the way we want it, build our healthcare the way we want it and build our economy the way we want it. Identity helps with that. Unity helps with that.