Insights from Ifá Divination Practice

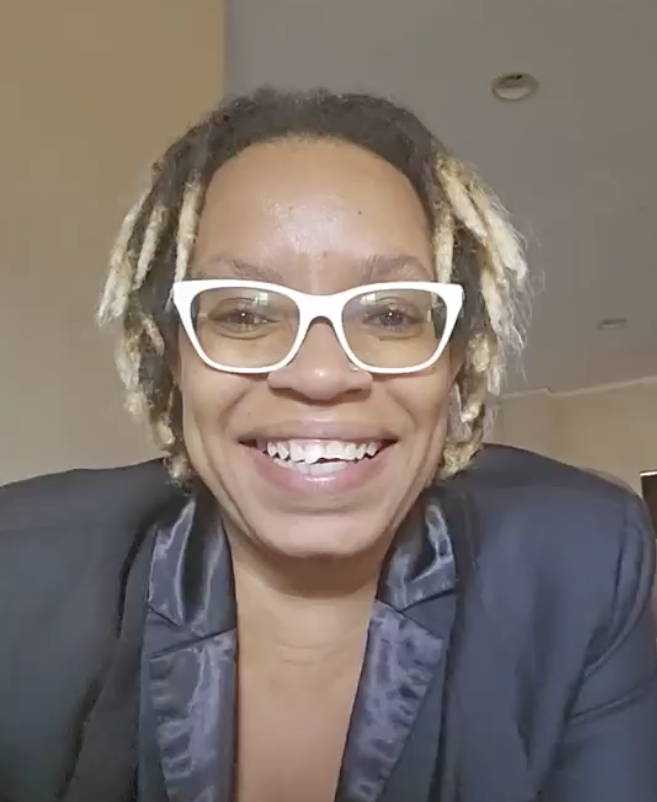

The Repair Campaign spoke with UWI Lecturer Janique Dennis-Prescott about her Ifá spiritual practice, and her views on the faith’s role historically and in the present-day reparatory justice movement.

February 29, 2024

Tell us about yourself, the work that you do and your faith background.

My name is Janique Dennis-Prescott and I teach academic literacies and literature at the University of The West Indies. I am also called a few other names as it relates to my Ifá practice. I am Iyanifá Ifá Yemisi, which means Ifá Priestess, Ifá takes care of me. And I am Iyalòrìṣà Okuta Iré, meaning Mother of the Òrìṣà, Blessed Stone.

As for my spiritual background, I’m initiated into Ifá, out of Yoruba in Trinidad and Tobago, and I’m initiated into Èṣù Elega, out of Santería in Cuba. As Omo Ifá, Omo Òrìṣà, I am a combination of Nigerian Yoruban Ifá and Cuban Santería Ifá but still have influences from being born and living in Trinidad and Tobago.

What is Ifá practice and where did it originate?

The Ifá practice is an umbrella concept for a number of divination systems born out of the Yoruba people. The Yoruba people were originally located in what is now known as Benin, Togo, and of course, Nigeria. Yoruba land is in Nigeria. As a result of the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans, we were moved to a lot of places. When the tradition moved, it was influenced by languages, cultures, laws, and oppression by colonisers so there have been various versions born out of our shared trauma.

We’re all branches of one tree, none greater or lesser than the other because we all function in our given socio-historical contexts. You have Santería out of Cuba, Candomblé out of Brazil, Spiritual Baptists, Ṣàngó Baptists, and the Òrìṣà, out of Trinidad and Tobago, and of course you have Voodoun out of Haiti. We are multitudes. We are everywhere and we are in everything.

For context, it’s important to also describe what an Òrìṣà is. An Òrìṣà is an entity that operates as one of a pantheon in the Yoruba system. There is one tripartite godhead – Olodumare, Olofin, Olorun – neither male nor female. And out of the Godhead was born these entities to function on our metaphysical plane – these entities are the Òrìṣà.

Many scholars, anthropologists and theologians, have described the Òrìṣà as deities. I avoid the term because there are a number of connotations that go with ‘deity’, and I would like to avoid those connotations as they are individual entities distinct from the godhead.

How does Ifá practice work and what are some of the key aspects of the faith?

In Ifá practice, there is a sacred text for every human being. It’s not one text; I have a text and you have a text. And when you make decisions that change the course of your life, your texts can change as well. The sacred text for you will say, now that you’re doing this, these are the things you should consider.

Central to understanding Ifá is that while it is based on communal living, the spiritual system of Ifá divination, in which we see past, present and future, is individual.

There are 256 Odu, which are like chapters in the Sacred Oracles of Ifá, and inside of each one of those, you have a number of Ese. You have to go to a high priest or priestess of Ifá, a Babalawo or an IyanIfá, who has been given the authority to divine for you and tell you what your sacred text is right now. That’s how Omo, children of Ifá, children of the Òrìṣà operate. We work on divinations.

All of divination works on a yes/no system, very much like computers – zeros and ones. It’s a systematic mathematical system, hence the number of Odu.

At the same time, when you undergo a major life experience, such as an initiation, you get an Odu for life. This is an Odu that tells you of your past, your present and your future: these are the things you never should do and the things you always have to do.

What misconceptions are there about Ifá practice and how would you clarify them?

There is an international misconception of Obeah as evil which comes from the fear of the unknown and the linguistic transformations that would have taken place over time. Appreciating the history can help to clear up some of these misconceptions.

The “Obi” is a palm tree which provides us an obi seed. This is sacred to Ifá as this obi seed is used in divination. It is so wonderfully sacred to us that there are exclamations when the obi lands in a favourable manner.

During chattel slavery, enslaved Africans would meet for church to mask the continuation of traditional spiritual practices. Church would go late into the night and when whomever was looking out had fallen asleep, they would begin their obi divination work. And when the obi would land in the way that we want it to, there would be an exclamation:

“OBI-O, OBI-AH!”

Meaning, we have gotten what we asked for – we are in sync. Everything is going to be fine.

Somebody overhearing what’s going on might say they’re doing the “Obeah” again.

Obeah and Voodoun are parallel systems to Ifá with parallel entities – they’re all part of the same tree.

In light of colonial violence, what role has Ifá practice played in the lives of the enslaved and in fuelling historical resistance movements?

When I was working as a research assistant, I decided to look at the Haitian Revolution and what I found changed my perspective of emancipation forever – I found that the Haitian Revolution was the result of a ritual. A ritual was performed in Haiti which called upon the Ogun – an Òrìṣà known for a number of presentations, one of them being war strategy. We have an idea of this very powerful entity as a protector, a warrior, a strategist. This entity’s job is to remove, eradicate, delete all enemies. There is no discussion about how to handle them. Ogun is going to take care of them.

The Ogun manifested and if you read about the Haitian Revolution, you know the rest of the story. As they say, it’s history.

Man, woman, child, streets, beaches, forest, everything covered in blood.

In light of its historical role, in what way do you think Ifá belief and practice inform today’s fight for reparatory justice for chattel slavery?

The fact that we as a people have survived physically is its own magic. As the word Sankofa implies, the fact that we have gone back to get and retain our identity, culture, language, spirit, ancestry and family, and have found some of ourselves after centuries, is magic.

The fact that we have Ifá in so many places where we have found ourselves. Magic.

Throughout our historical revolutions, we would have needed many forms of Òrìṣà. And in our contemporary ‘(r)evolution’, just as in our magical survival, we’re going to need all of them again as they all serve different functions.

As to whether or not Ifá should be a part of this, I think the answer is, as always, Ifá should be consulted. Omo Ifá know that when the ori is unclear, we consult Ifá. We would need a council of elders to consult and say what Ifá says and dictate what, if anything, has to be done or if there is a way forward. There are councils of elders globally that can be called. You can consult the elders and the elders will let you know what Ifá says. But Ifá has to voice Ifá. A human being cannot speak for Ifa – only communicate what Ifa says.

What is your hope for the future?

I hope for a better world. I hope for a safe environment, physically and socially, for our children and our grandchildren. I hope for an elevation of our intellectual and spiritual selves, so that we develop into better beings and critical thinkers focused on making a positive impact in our environment and the people around us and around the world.

We have to learn how to be more emotionally intelligent, spiritually connected, financially intelligent, socially wise to make our efforts relevant to human capacity development.

We are still carrying around, in our blood, the traumas of our ancestors. We have a lot of pain, sorrow and unresolved issues that we need to look at. And I think it’s really important that the entire reparations discussion include psychological rehabilitation and an exposure to traditional African systems and spiritual systems.