Between Radicalism and Repression: Walter Rodney’s Revolutionary Praxis

The following article was written by Dr Charisse Burden-Stelly and originally appeared in Black Perspectives on May 6, 2019.

Dr Burden-Stelly is a critical Black Studies scholar and Associate Professor of African American Studies at Wayne State University.

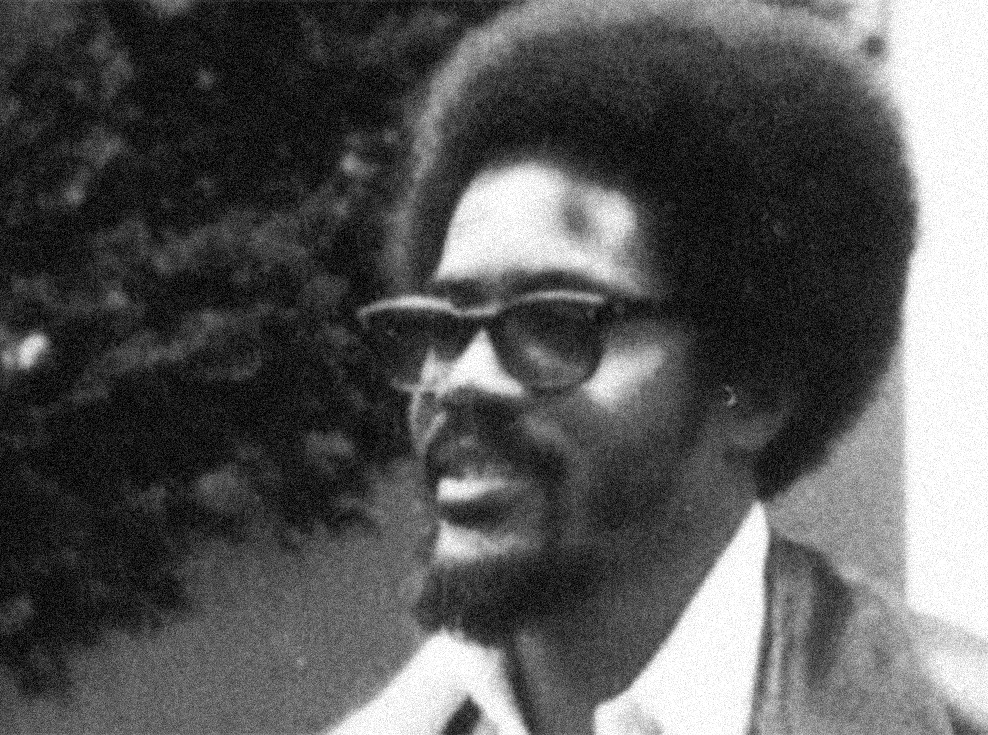

On June 13, 1980, the Black Marxist, Pan-Africanist, historian, and scholar-activist Walter Rodney was assassinated in Georgetown, Guyana.1 That year, students and faculty at the University of Dar es Salaam, where he taught for eight years, demanded the university confer upon him a posthumous honorary degree. They insisted that his dedication to the cause of Third World liberation, his support for freedom struggles in Southern Africa against Portuguese colonialism and white supremacist regimes, his immense contribution to transforming the university into a progressive institution, his unparalleled intellectual work excavating the impact of enslavement, colonialism, and imperialist oppression on African people, and his struggle against the repressive and “tyrannical” Burnham regime, among many other contributions, made him ideally suited for such an honor.2

One year later, an article titled, “Walter Rodney—Son of Mankind” published in the West Indian Digest described this freedom fighter in the following way: “From time to time an individual embodies and personifies the collective expression of a class, a race, or a people struggling to be free. Walter Rodney embodied this quest, but with the kind of humility and honesty which endeared him to all those who came in contact with his ideas.”3

As these two examples demonstrate, the global Black community was angered and disgusted by Rodney’s politically-motivated execution and understood it to be a form of imperialist aggression meant to stifle and undermine revolutionary insurgencies in Guyana and throughout the Third World more broadly. As one Nigerian paper opined, the assassination of Walter Rodney demonstrated that “Forbes Burnham and his paymasters have failed to learn some of the critical lessons of the recent history of the anti-imperialist struggle in Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the world”—namely, that by eliminating a “genuine people’s leader” the imperialists had intensified the resolve of the masses in their struggle against domination.4 Not unlike Black stalwarts including Paul Robeson, Vicki Garvin, Steve Biko, and Shirley Graham Du Bois, Walter Rodney’s life was constituted by a feedback loop of theory and practice and the dialectic between radicalism and repression.

Some of Rodney’s most important contributions to the Black Liberation Movement were his explication of, and mobilization against, oppression and exploitation emanating from the interrelations of imperialism, (neo)colonialism, and white supremacy. He understood colonialism to be a form of political rule that was one facet of the larger imperial process; on the African continent, colonial rule reflected deeper forces of domination and dispossession that fundamentally transformed the mode of production and social relations therein. Neocolonialism, by contrast, was the reality that when freedom from “White man’s rule” had ostensibly been achieved, the material conditions of most Africans did not radically alter, the cultural conditions were not significantly transformed, and the political and social structures merely transitioned from the possession of one ruling class to another. Given this distinction, anti-colonialism and anti-neocolonialism took on a different character. He explained: “…When I was in Jamaica in 1960, I would say that already my consciousness of West Indian society was not that we needed to fight the British but that we needed to fight the British, the Americans, and their indigenous lackeys. That I see as an anti-neo-colonial consciousness as distinct from a purely anti-colonial consciousness.”

Furthermore, the association of wealth with whiteness and poverty with Blackness, Rodney contended, was a manifestation of the imperialist relationship that was constituted by not only white supremacy, but also the expropriation of the colonies to enrich the metropoles. Thus, the very idea of development was inexorably bound up with racist logics; as he wrote in “African History and African Development Planning,” “…A racist streak is never far from the surface in bourgeois presentations on the problems of development, because non-European people are equated with backwardness and stagnation, while progress is uniquely European.” Even worse, this racist devaluation had resulted in the negative self-evaluation of many Africans, especially those of the petty bourgeoisie.5

Rodney also understood the United States and the Caribbean to be constitutively racist given the relationship between enslaved Africans and slave masters and the way this relationship codified labor. Likewise, he regarded the United States as the only nation in history in which its revolutionary leaders fought against colonialism, only to “build a contradiction into their society by explicitly denying human dignity to a quarter of the population they aspired to govern.” This was not least because racism, as the superstructure of ideas, was instrumental to the functioning of the economic base.6

Rodney’s work in a number of organizations, including the Institute of the Black World (IBW), the Working People’s Alliance (WPA), and the Council for the Development of Economic and Social Research in Africa and the International Congress of Africanists (CODESRIA), complimented his rigorous analysis. In his praxis, he emphasized the importance of African liberation, socialism, workers’ rights, anti-racism, and the responsibility of academics and leaders to serve the masses of Black people.

For example, at the Third International Congress of Africanists, Rodney and his comrades passed the “Resolution on the Armed Struggle in Southern Africa” in which they excoriated the indifference of most Africanists toward liberation struggles in Southern Africa and affirmed the necessity of commitment to African liberation for those engaging in the study of Africa. Signatories also condemned Portuguese colonial aggression in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau; white minority oppression in South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe; and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, capitalist, and corporate financial and military assistance to—and thus support for—the continuation of colonialism, imperialism, and apartheid. Showing their solidarity with African emancipation efforts, they applauded progress made in Southern Africa on the battlefront, steps toward implementing social programs in liberated areas, and the heightened political consciousness and organizing of combatants. Moreover, Rodney and his peers welcomed the recent independence of Guinea-Bissau and the continued material and moral support being offered by African and outside nations, particularly the socialist ones, and by Liberation Support Committees and other international organizations.7

Like W.E.B. Du Bois, Claudia Jones, William Patterson, and many other Black revolutionaries, Rodney was punished for his radicalism. In 1968 he was refused re-entry into Jamaica for ostensibly attempting to spread “Castro-style” revolution, precipitating what came to be known as the “Rodney riots.” In 1974 his appointment to the University of Guyana was cancelled, and in September 1979 he was arrested and accused, along with other WPA members, of burning down the People’s National Congress headquarters. His home was ransacked by government officials and political literature was confiscated. He was also banned from international travel while he awaited trial.

Rodney’s assassination in 1980 underscored the fundamental threat his love for African people, his push for the end of imperialism, his analysis of neocolonialism, and his belief in socialism posed to U.S. domination, Western hegemony, and Global South leaders committed to perpetuating racist-imperialist capitalism.

Sources

1. “Background to a Murder.” NACLA November 25, 1980, Walter Rodney Papers, Box 1 Folder 7, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

2. “We, the students and members of staff at the University of Dar es Salaam,” July 22, 1980, Walter Rodney Papers, Box 1 Folder 11, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

3. “Walter Rodney—Sone of Mankind,” West Indian Digest, March 1981, Walter Rodney Papers, Box 1 Folder 7, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

4. Segun Osoba, “In Memory: Walter Rodney,” Positive Review 1, no. 4 (Jan-Feb 1981): 32-37, Walter Rodney Papers, Box 1 Folder 11, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

5. Walter Rodney, “African History and African Development Planning,” (unpublished), Walter Rodney Papers, Box 13 Folder 2, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

6. Walter Rodney, “Aspects of Capitalist and Socialist Development in the U.S.A.,” (unpublished), Walter Rodney Papers, Box 13 Folder 19, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.

7. “Resolution on the Armed Struggle in Southern Africa,” n.d., Walter Rodney Papers, Box 4 Folder 41, Archives Research Center Atlanta University Center.